For our last segment of memorable moments from the silver screen, we’re delving into the early years of contemporary cinema. Like most forms of art, the ‘90s and ‘00s films were the works of devoted cinephiles, enriched with nods to now-legendary directors such as Jean-Luc Godard, Alfred Hitchcock, and John Huston, to name but a few. This period also saw the splendiferous rise of Asian cinema, along with the sunset of epic directorial careers and the sunrise of new talents.

1994: For the Love of Classics

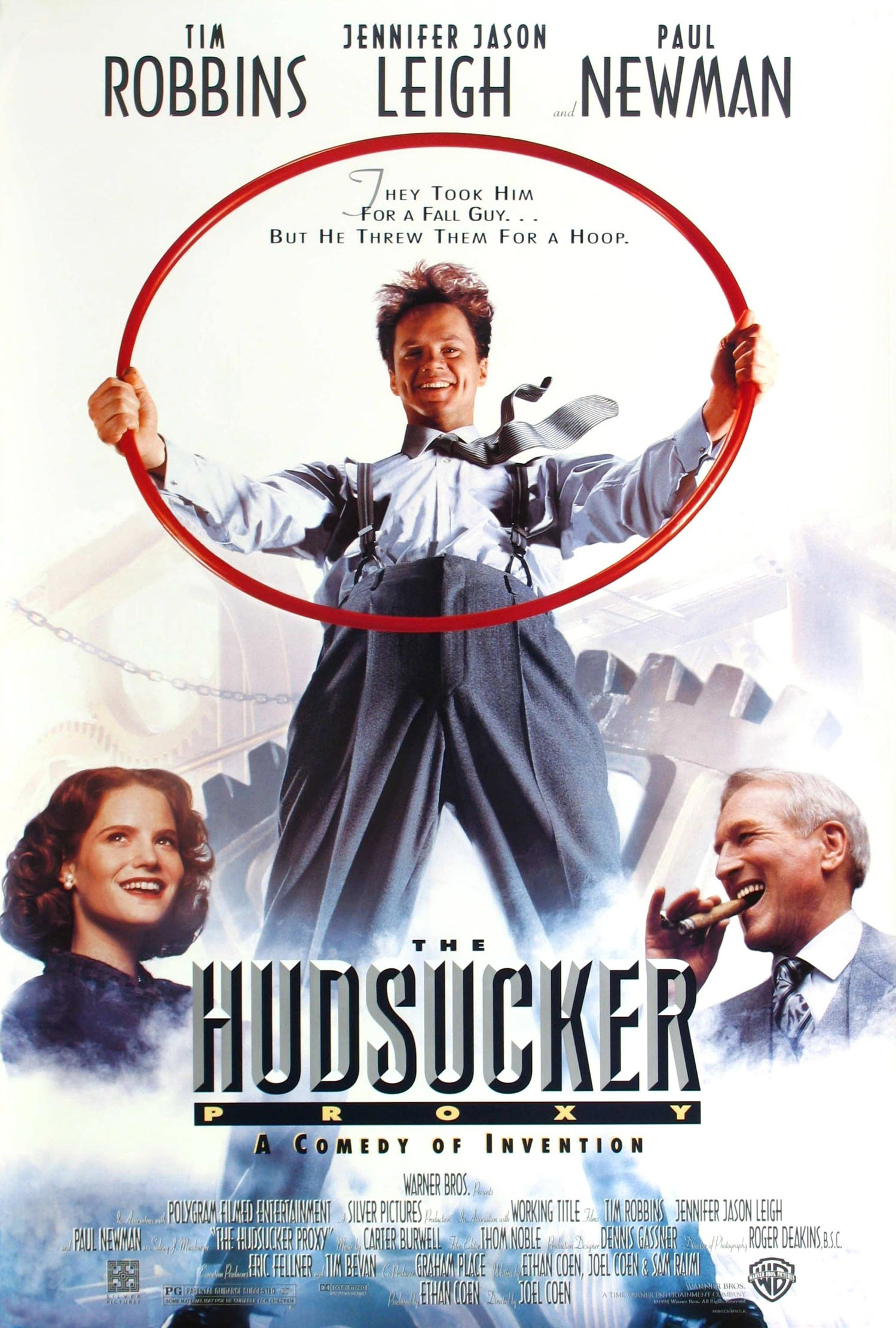

In the early days of Joel and Ethan Coen, exploiting the ridiculous to depict the rise of America as we know it was a new technique for intelligent comedy. In ‘The Hudsucker Proxy’ (1994), the Coens envisage Dwight Eisenhower’s United States as a gargantuan bureaucracy that is hungrily devoted to the pursuit of money, power, and fame. Using imagery and editing often reminding us of Soviet classics such as Eisenstein, the directors seem to have some crazy fun by poking the near-totalitarian conformism that more or less defined Post-War America. The film commands repeat viewings for its subtle and resonant use of circular motifs—the star of these being the hula hoop, of course.

‘THE HUDSUCKER PROXY’ (1994), ©POLYGRAM FILMED ENTERTAINMENT

‘THE HUDSUCKER PROXY’ (1994), ©POLYGRAM FILMED ENTERTAINMENT

The debut of Turner Classic Movies marked the beginning of cinephilia’s mainstreaming. It started out as a low-concept cable premise, the showcase channel of a gazillionaire’s back catalogue of film titles, and as a competitor for the then-dominant American Movie Classics. It basically turned Ted Turner, purveyor of hideously colorized home video, into a friend of movie lovers worldwide. Turner Classic Movies also brought forth the value of considering a film’s topic thanks to the intros and outros of Robert Osborne. TCM was not a hub of revolutionary film criticism, however.

To this day, its selections aim for an institutional, high quality approach, while Osborne’s commentary is peppered Hollywood gossip, at best. But the high standards of the networks and its demands of a 24-hour cycle have led to a broad selection of film titles, including silent and foreign language pictures.

©RICK MAIMAN

©RICK MAIMAN

One of the best things to come out of 1994, however, was the exquisitely pulpy ‘Pulp Fiction’ by Quentin Tarantino. The watch monologue especially represents the uniquely talented director at his best. Here, Christopher Walken’s Captain Koons delivers a watch to Butch, the kid who will grow up to become the boxer Butch portrayed by Bruce Willis. He explains that the watch belonged to Butch’s father, passed down from his grandfather and great-grandfather.

In western cultures, particularly, the watch a son inherits from his father is an item of great significance, representing the phallus transferred from one patriarchal generation to another. The history of this specific timepiece is also the history of 20th century America, from WWI to Vietnam, represented by its wearers. Then Tarantino has Koons expose the true nature of his symbolism by revealing that Butch’s father hid the watch ‘in the one place he knew he could hide something’. That place where the sun doesn’t shine.

‘PULP FICTION’ (1994), ©MIRAMAX

‘PULP FICTION’ (1994), ©MIRAMAX

1996: The Birth of DVD

A very Nineties sort of thing was to use music not as a soundtrack or as a comment, but rather as a pure stimulant. Danny Boyle does an exquisite job of that with Underworld’s ‘Born Slippy’ in ‘Trainspotting’ (1996). The film itself was mostly about the squalors and fitful glories of heroin abuse, but the timing of its release and its grimy, buzzing energy, along with its use of the aforementioned song pushed ‘Trainspotting’ at the peak of an emerging culture—Generation Ecstasy.

But 1996 had something greater to give besides Danny Boyle’s oeuvre. On 1st November, the first DVD players went on sale in Japan. This advent of digital video disks (or digital versatile disks) was a case study in the way simple marketplace competition can enrich an entire culture. At the time, studios were faced with the challenge of getting their sceptical home viewers to upgrade from their trusted VHS tapes to a whole new format. The solution came in two equally convincing forms.

The first signalled the beginning of the end for the likes of Blockbuster Video, claiming that the VHS format was garbage and the rental-store economy that supported it was insane. The second proposed that by increasing the value of home video, one could turn the DVD into a sell-through rather than a rental product. It led to an explosion of commentary tracks, outtakes, alternate versions, critical histories and so on. Read-only media like the DVD ultimately expanded the participatory element of entertainment, and this culture of engagement is one of the twentieth century’s final gifts to us.

1997: The Inestimable Value of Pam Grier

When looking at Quentin Tarantino’s career, one would have to admit that his greatest film is also the one with believably human characters. Each of his works proves why he’s the king of pop-culture pastiche, but only ‘Jackie Brown’ (1997) comes fitted with a heart of its own. Here, Tarantino manages to conceive two characters who resemble human beings with a believable emotional life.

‘Jackie Brown’ captures our attention through the love story between its titular stewardess and the bail bondsman, a love story that also serves as the meeting point between two styles of medium cool—‘70s blaxploitation, as represented by Pam Grier, and ‘60s thriller, offered by Robert Forster. It is a counterpoint, as well, to the ironic detachment that usually surrounds Tarantino’s classically meta-characters, though Samuel L. Jackson does a fine job of holding a banner for them as the eccentric, vampiric gangster.

There is something about ‘Jackie Brown’ that just stands out, even after all these years. My guess is that it comes from the uncommon respect with which Tarantino treats Ms Grier, as well as the remarkable shots with which she leads the entire movie—her mature beauty and her aura of self-respect both captured with admiring tenderness.

‘JACKIE BROWN’ (1997), ©MIRAMAX

‘JACKIE BROWN’ (1997), ©MIRAMAX

1998: Of Long and Complex Opening Shots

As with previous studies of cinematic history, it would be damn near impossible to dissect every movie moment that made its mark. Sacrifices must be made, along with painful cuts. But I wouldn’t be able to skip past this year without mentioning the tour de force that is the opening scene of Brian De Palma’s ‘Snake Eyes’ (1998).

It’s one of the longest and most difficult shots ever brought to the big screen—full of characters and anonymous moving crowds, rife with movements in so many directions that the viewer eventually forgets it’s a single continuous tracking, panning, and craning shot. Mr De Palma, author of ‘Dressed to Kill’ (1980), ‘Blow Out’ (1981), and ‘Body Double’ (1984), seems obsessed with telling his audience to look harder, look better, look twice.

As Miguel Marias once wrote, ‘you think you have understood more than you did, while you are unable to see much of what is shown to you, which you either underestimate or overlook or forget or, on the contrary, take for granted as the truth, jumping to conclusions or overinterpreting details’.

‘SNAKE EYES’ (1998), ©PARAMOUNT PICTURES

‘SNAKE EYES’ (1998), ©PARAMOUNT PICTURES

1999: A Most Extraordinary Year

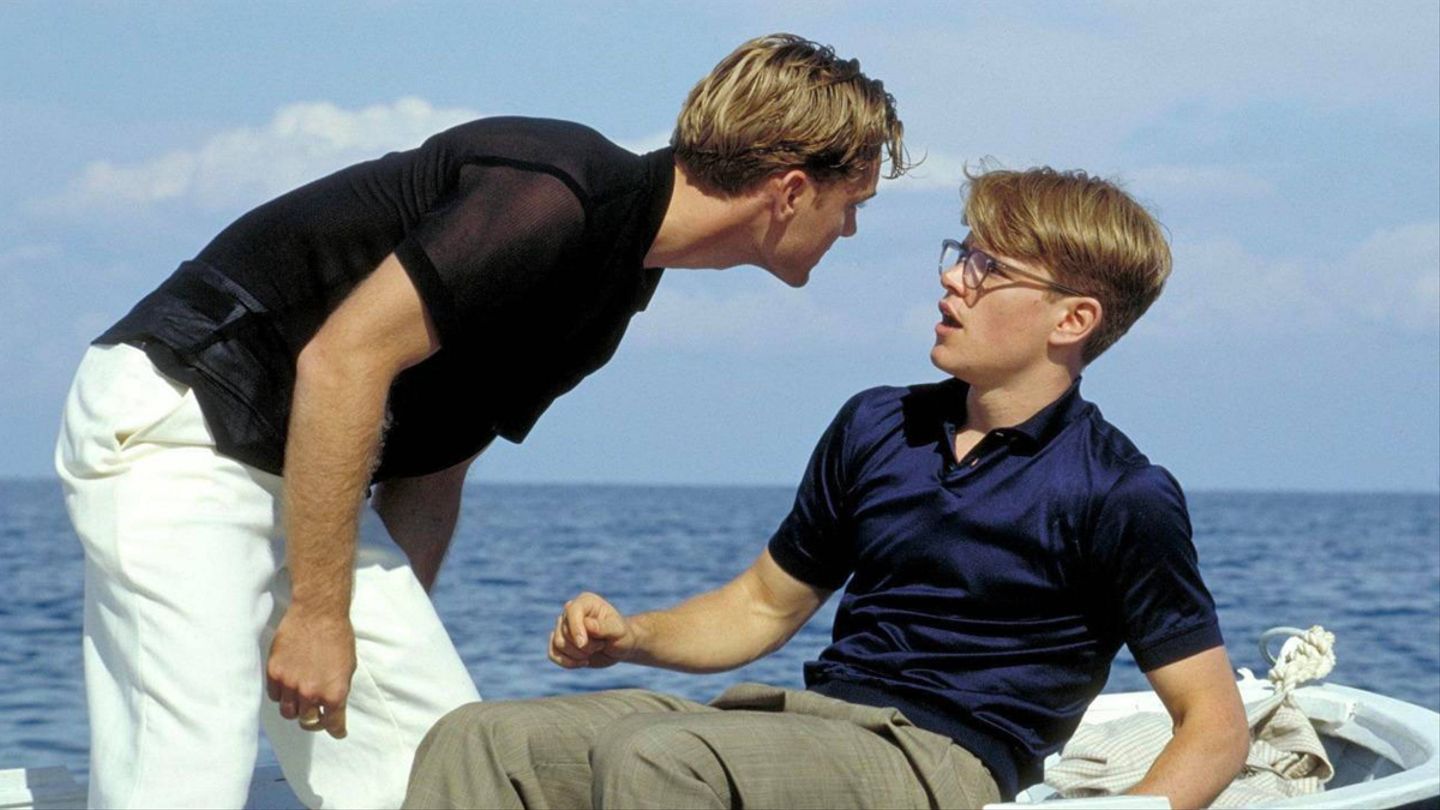

Incredible things came at the end of the 20th century. Wonderful things. Cinematic masterpieces and turning points in this ever-evolving medium. One scene worth mentioning as a mere hors d’oeuvre would be Dickie’s murder in ‘The Talented Mr Ripley’ (1999) by Anthony Minghella. Here, the director offers a superb portrait of class distinction and masculine violence—the latter fuelled by unrequited love. It builds slowly from a subtle disagreement through Dickie’s arrogant superiority clashing with Tom’s mortified self-negation, culminating with an instant of uncontrollable release. Tom doesn’t hate Dickie, he worships him. And his god has just declared him unfit. In a sense, the killing is less murder and more suicide, as Tom, the proficient imitator, will now take Dickie’s passport and transform himself.

‘THE TALENTED MR RIPLEY’ (1999), ©MIRAMAX

‘THE TALENTED MR RIPLEY’ (1999), ©MIRAMAX

Stanley Kubrick’s last film, ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ (1999), lacked critical and commercial support to a level that proved just how low the cineplex had sunk in that era. Its mere existence was an insult to the audience, who’d expected to see something flashier and easier to digest from the likes of Nicole Kidman and Tom Cruise, whom they’d drooled over during ‘Days of Thunder’ (1990). Kubrick’s fluid camera work lulled viewers. The modulated performances felt wasteful to them. The portrayal of New York at Christmas as a lonely city of sexual conspirators seemed fake. In a sense, ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ was the death of the auteur film made to look like a marketing accident—an insult to the director who passed away four months before its theatrical release.

George Lucas’s ‘Star Wars I: The Phantom Menace’ (1999) may have lacked in many other aspects when compared to the first three films of his Star Wars saga, but its one redeeming quality rests in the lightsabre duel. It was sorely needed after the anaemic confrontation between Sir Alec Guinness’s Obi-Wan Kenobi and David Prowse’s Darth Vader. The final Jedi showdown of ‘The Phantom Menace’ is poetry in motion, put together by the combined synergy of stunt coordinator Nick Gillard, assistant Andreas Petrides, and actor/stuntman/martial arts champion Ray Park. Not only did they give the lightsabre duel the treatment it deserved, they delivered the most invigorating example of swordsmanship in Western cinema since the age of Douglas Fairbanks and Errol Flynn, further enhanced by John Williams’s nervous score.

‘STAR WARS I: THE PHANTOM MENACE’ (1999), ©LUCASFILM

‘STAR WARS I: THE PHANTOM MENACE’ (1999), ©LUCASFILM

Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez created ‘The Blair Witch Project’ (1999), propelled to worldwide fame thanks to cinema’s newly discovered cousin, an adjunct and a marketing tool rolled up into one: the Internet. Much like James Hogg’s publicity stunt of 1823 regarding ‘The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner’, ‘The Blair Witch Project’ came to us claiming to be the lost footage of three filmmakers who mysteriously disappeared after an encounter with something nebulous and supernatural in the woods. The film’s website and the tie-in pseudo-documentary ‘Curse of the Blair Witch’ further added value to the story with historical background that just made it feel so real. It represented the birth of the ‘found footage’ style that still works for the supernatural horror genre.

‘THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT’ (1999), ©HAXAN FILMS

‘THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT’ (1999), ©HAXAN FILMS

After the first computer-generated imagery made its debut with ‘Westworld’ (1973), and the virtual forms entered the public consciousness through ‘Tron’ (1982), the Wachowski Brothers took the art of special effects and computer graphics to a whole new level with ‘The Matrix’ (1999). Visual effects designer John Gaeta went to great lengths for this film’s ‘Bullet time’ money shot by attaching hundreds of still cameras to a snaky metal rig. Each of these units generated a single frame when fired in sequence, in a Muybridge-motion-study style, around a flailing or jumping actor. When the images were later stacked like a flipbook in computerized form, the result gave us Keanu Reeves’s Neo dodging bullets in slow motion while the viewers swirled around him like the eye of God. This moment changed the way cinema worked, making the unrealized potential of digital effects into a most wonderful reality.

‘THE MATRIX’ (1999), ©WARNER BROS.

‘THE MATRIX’ (1999), ©WARNER BROS.

2000: The Most Visually Stylish Films Arise

No one will ever forget the bamboo forest fight in Ang Lee’s ‘Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon’ (2000). Each fight scene reveals a different emotion in this movie, and the bamboo grove moment between Chow Yun-fat’s Li Mu Bai and Zhang Ziyi’s Jen is truly exquisite. A number of elements—the rhythmic cutting, the music, the affective close-ups, the coming together in one move and drawing away, his enormous tenderness measured against her rebelliousness—they all turn this encounter of fighting skills into a love scene of sorts.

Equally enthralling, ‘In the Mood for Love’ (1999) by Wong Kar-Wai made movie magic with its subtle eroticism and artful visuals. Following two neighbours who discover their spouses’ extramarital affairs and get closer to one another, the Hong Kong Second Wave filmmaker accomplishes something extraordinary by showing us how ‘it’s already happened’ before our eyes. But the summit of this masterpiece comes with the scenography and the prevailing colours which intensify the emotions, shamelessly yet elegantly suggestive of an erotic and passionate atmosphere. In the beginning, Mrs Chan’s dresses are mild in their design and palette, but once she and Mr Chow start seeing each other, warmer colours, of which red is predominant, begin to dominate the screen.

‘IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE’ (2000), ©BLOCK 2 PICTURES

‘IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE’ (2000), ©BLOCK 2 PICTURES

2002: The Mexican Cinema Revival

There have been great Mexican directors since the ‘30s, surely. Emilio Fernández, Fernando de Fuentes and Luis Buñuel are but three of the Latin-American filmmakers that have gifted us with great movie moments. However, Alfonso Cuarón’s ‘Y Tu Mamá También’ (2002) signifies a new era for Mexico’s film culture. Gael Garcia Bernal’s Julio and Diego Luna’s Tenoch kiss scene takes a dig at Mexican machismo and homophobia without any fear—in the film, it leads to the destruction of the male characters’ friendship.

In a country so completely divided by class most of all, where social mobility is extremely limited, the fallout from that kiss seems powered by class anxiety, as well. The young men’s friendship bridges an economic abyss in Mexican society. Therefore, it cannot survive. Far from being an Americanisation, ‘Y Tu Mamá También’ is one of the most revealing Mexican films ever made.

‘Y TU MAMÁ TAMBIÉN’, ©ANHELO PRODUCCIONES

‘Y TU MAMÁ TAMBIÉN’, ©ANHELO PRODUCCIONES

2004: 21st Century Cinema

After 2001, the world wasn’t the same again. Something happened after 9/11, something that weaved itself through the way stories were told. But none of the films inspired by those terrible events had a greater impact than Michael Moore’s documentary ‘Fahrenheit 9/11’ (2004). And while moviegoers may have strong positive and negative opinions about the director, his filmmaking savvy should be appreciated once it’s considered alongside the overall thrust of his politics. His weakness for tendentious argument and first-person showboating should also be noted.

We all remember his rendition of George W. Bush in the schoolroom, however. It shows us a president who’s just been told the second plane has hit the Twin Towers, and he chooses to go ahead with his photo-op at a Florida school. Noting that Bush’s failure to do anything (even leave the room for information) lasted for almost seven minutes, Moore wonders if the vacation-loving president were wishing he’d gone to work more often. By the time this part of the monologue ends with a mention of the cuts that Bush applied to the FBI’s terrorism funding, the image of his paralysis has become indelible. I doubt it will ever lose its ghastly strength even now upon another viewing, long after the Bush administration has become history.

‘FAHRENHEIT 9/11’, ©FELLOWSHIP ADVENTURE GROUP

‘FAHRENHEIT 9/11’, ©FELLOWSHIP ADVENTURE GROUP

But let us not end this series on a sombre note. Instead, I invite you to remember Richard Linklater’s ‘Before Sunset’ (2004), starring the inimitable Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy in two of their most memorable roles. Much like its predecessor, ‘Before Sunrise’ (1995), the film is focused on the fleeting hours, minutes, and seconds before Jesse and Celine must end their brief encounter. If the two were in a foreign place (Vienna) in the previous story, Jesse now finds himself on Celine’s territory in Paris, on a publicity tour that fictionalizes their previous experience.

‘BEFORE SUNSET’ (2004), ©WARNER INDEPENDENT PICTURES

‘BEFORE SUNSET’ (2004), ©WARNER INDEPENDENT PICTURES

It is the end that stands out. The cab is waiting, and a plane will soon be boarding, ready to take Jesse away, but he shows no sign of getting off Celine’s couch. Instead, he chooses to enjoy her mimicking of a performance by Nina Simone—a show in which the singer took ‘all the time in the world’. Suddenly, in this tension of a looming deadline, Jesse and Celine seem to have all kinds of time. The future is, once more, free and open to them.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

Cinematic History and Its Defining Moments: 1983-1993

Going into the modern chapters of film history, we will observe a rapid development of special…

Cinematic History and Its Defining Moments: 1972-1982

The Seventies and early Eighties were an era of experiments on the silver screen. With new…

Cinematic History and Its Defining Moments: 1961-1971

As technology and storytelling evolved, the second half of the twentieth century brought forth a…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.