Before movies, our primary source of dramatic entertainment came from radio shows and theatre. The latter, in fact, is one of the oldest performing arts, with twisty roots dating back as far as classical Athens of 6th century BC, where the vibrant tradition of theatre first blossomed and expanded throughout the world. At first, writing for the stage and writing for the screen were mistaken as similar, though soon it became obvious that the audiences’ attention spans differed critically from one form to the other.

Aside from the physical restrictions, the stage environment is vastly organic. Theatre is a nurturing art form, with adequate rehearsal time, strong bonds between anchors, and the possibility of experimenting with the director up to days before opening night. This fluidity doesn’t survive into the editing room of a film. Therefore, theatre plays and film scripts read differently. Yet sometimes, they will meet somewhere in the middle and even cross into each other most beautifully.

And while there have been many actors who moved successfully from the stage to the silver screen—Judi Dench, Laurence Olivier, Meryl Streep, Marlon Brando, and Paul Newman, to name but a few—I find that there are few plays that have done the same.

‘HAMLET’ (1996), ©CASTLE ROCK ENTERTAINMENT

‘HAMLET’ (1996), ©CASTLE ROCK ENTERTAINMENT

Among the directors who have tried to bring theatre into film, I must mention Kenneth Branagh as champion, since he is responsible for bringing a plethora of Shakespeare’s work to cinema. His version of ‘Hamlet’ (1996) was better than Franco Zeffirelli’s star-studded feature of 1990, for example, and his love for the drama stage has had him bouncing between the two visual art mediums for years, his theatre company productions renowned worldwide and constantly sold out.

An especially popular source material for the screen has been William Shakespeare. Almost all of his plays have found their way in front of cameras, one way or another, though easier to remember to this day is ‘Romeo & Juliet’, a darling of equally prolific directors Franco Zeffirelli and Baz Luhrmann. The English playwright’s works have been done either mot-à-mot by traditionalists, some of whom struggled with the tongue-twisting dialogues or revamped and repurposed for younger generations by Hollywood’s lesser-known underdogs.

While I am happy to cheat again with honourable mentions (read recommendations) such as ‘Steel Magnolias’ (1989), directed by Herbert Ross and based on the eponymous play by Robert Harling; ‘Casablanca’ (1942), directed by Michael Curtiz and based on the play by Murray Burnett and Joan Alison, originally titled ‘Everybody Comes to Rick’s’; ‘On Golden Pond’ (1981), directed by Mark Rydell and based on Ernest Thompson’s play; and ‘Suddenly Last Summer’ (1959), directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz and based on one of Tennessee Williams’s plays… Sorry. That was shameless.

Allow me to tell you about my absolute favourite plays that were not only successfully adapted for the screen, but stylishly transplanted as self-contained masterpieces.

‘STEEL MAGNOLIAS’ (1989), ©TRISTAR PICTURES

‘STEEL MAGNOLIAS’ (1989), ©TRISTAR PICTURES

‘One Night in Miami’ (2020)

Regina King’s recent directorial debut is a carefully calculated and elegantly executed work of theatre brought into film. Headlined by a ridiculously talented cast, the story revolves around one fictional account of a real night when four powerful figures of the Civil Rights Movement met at the Hampton House in Miami.

Kingsley Ben-Adir is brilliant as Malcolm X. Eli Goree delivers a Cassius Clay as real as the World’s Greatest himself. Aldis Hodge is impressive as Jim Brown, star footballer-turned-movie-star. And Leslie Odom Jr.’s rendition of the inimitable Sam Cooke is simply out of this world—with the voice of an angel, no less! Much like the original, ‘One Night in Miami’ is a profound conversation about race, social justice, and the constant struggles of Black Americans in a society that treated them as lesser citizens for too long. Most importantly, Regina King’s take on Kemp Powers’ 2013 play is an emotionally gutting one, powered not only by the performances but by the writing and Tammy Reiker’s distinguished cinematography.

‘ONE NIGHT IN MIAMI’ (2020), ©ABKCO FILMS/SNOOT ENTERTAINMENT

‘ONE NIGHT IN MIAMI’ (2020), ©ABKCO FILMS/SNOOT ENTERTAINMENT

‘A Few Good Men’ (1992)

Much like Kemp Powers, also known for his screenwriting work on ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ (2017) and ‘Soul’ (2020), Aaron Sorkin has found himself comfortable penning plays, films, and illustrious TV series alike. ‘A Few Good Men’ was the one that made a truly lasting impression upon its adaptation, under the helm of Rob Reiner.

It was nominated for four Academy Awards, offering incredible performances from a young Tom Cruise, a ferociously talented and wide-eyed Demi Moore, and the grand master of quotable movie lines during Trivia Night, Jack Nicholson. The courtroom thriller proved itself equally enthralling regardless of transposition method, showing Reiner at the top of his game.

‘A FEW GOOD MEN’ (1992), ©COLUMBIA PICTURES

‘A FEW GOOD MEN’ (1992), ©COLUMBIA PICTURES

‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ (1951)

There is a reason why Tennessee Williams, one of America’s foremost playwrights alongside Eugene O’Neill and Arthur Miller, was such a hit with Hollywood. His plays have a way of digging deep into the darkest, hottest pits of human nature, of bringing out the best and the worst from his characters. He put most of his tormented life onto the stage, using theatre as a form of expressing his truest self.

The legendary Elia Kazan, director of many of Williams’ plays, for that matter, said of him: ‘Everything in his life is in his plays, and everything in his plays is in his life’. ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ is a tempestuous work of dramatic art that brought Academy Awards to Vivien Leigh and Kim Hunter, accompanied by respectful nods to Mr Kazan’s directorial accomplishment and Marlon Brando’s spectacular acting.

‘A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE’ (1951), ©WARNER BROS.

‘A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE’ (1951), ©WARNER BROS.

‘Cat on a Hot Tin Roof’ (1958)

The ‘50s and the ‘60s were a lush period for theatre-to-film experiments, demanding that screen actors push themselves further and further until they were awarded accolades and golden statuettes. One of those thespians was Elizabeth Taylor, and ‘Cat on a Hot Tin Roof’ would not be her only foray into such bold projects. Today, she is remembered for multiple theatrical-style performances, including Franco Zeffirelli’s ‘The Taming of the Shrew’ (1967) of William Shakespeare and ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’ (1966) of Edward Albee.

But it was her sizzling portrayal of Maggie alongside Paul Newman’s Brick that garnered endless rounds of applause, in part thanks to Richard Brooks’ ability to transform one of Tennessee Williams’s most popular plays into a veritable crown jewel of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

‘CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF’ (1958), ©AVON PRODUCTIONS

‘CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF’ (1958), ©AVON PRODUCTIONS

‘Throne of Blood’ (1957)

While I did drone on a bit back there about the many adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays and as we keep running into the guy, it would be unethical of me not to include Akira Kurosawa’s outstanding drama, which rips ‘Macbeth’ from Medieval Scotland and sews it into the troubled canvas of feudal Japan. The iconic director added significant tweaks of his own, including a modified finale and Noh drama elements—not an easy feat to accomplish, considering the overall pathos of Kurosawa’s screenplay.

Creative liberties aside, Toshirô Mifune and Isuzu Yamada’s portrayals of the Japanese Macbeth and Lady Macbeth ultimately set the film farther apart. Kurosawa adored Shakespeare’s work and had been eager to adapt it for years, but Orson Welles’s ‘Macbeth’ (1948) came out and forced him to wait before making his own version.

‘THRONE OF BLOOD’ (1957), ©TOHO COMPANY

‘THRONE OF BLOOD’ (1957), ©TOHO COMPANY

‘Fences’ (2016)

While it isn’t Denzel Washington’s first directorial incursion, it is certainly his best, right after ‘Antwone Fisher’ (2002) and ‘The Great Debaters’ (2007). ‘Fences’ is based on the 1985 play by August Wilson, which is set in the 1950s and explores the Black American experience and examines the country’s difficult race relations. Mr Wilson earned a Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1987 for this magnificent contribution to American theatre. Naturally, the film adaptation aimed to do the same.

It brought Viola Davis an Academy Award and a Bafta Award for her performance, and the film garnered nominations for Best Motion Picture, Best Actor, and Best Adapted Screenplay—posthumously for August Wilson. One aspect of its success is likely to stem from Mr Washington’s previous work with the source material on Broadway, which gave him significant confidence to direct.

‘FENCES’ (2016), ©BRON STUDIOS

‘FENCES’ (2016), ©BRON STUDIOS

‘Amadeus’ (1984)

Milos Forman’s classic motion picture has a lengthy theatrical history. The play on which it is based was written by Peter Shaffer and first performed in 1979, inspired from an earlier short work by Alexander Pushkin from 1830, titled ‘Mozart and Salieri’, which was also used by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov as the 1897 libretto for an opera of the same name.

With Shaffer adapting his work for the screen and Forman directing—not to mention F. Murray Abraham and Tom Hulce’s dazzling performances as Antonio Salieri and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, respectively, it’s no wonder that the film was a triumph that took home not one, not two, but eight Academy Awards.

‘AMADEUS’ (1984), ©AMLF/THE SAUL ZAENTZ COMPANY

‘AMADEUS’ (1984), ©AMLF/THE SAUL ZAENTZ COMPANY

‘Glengarry Glen Ross’ (1992)

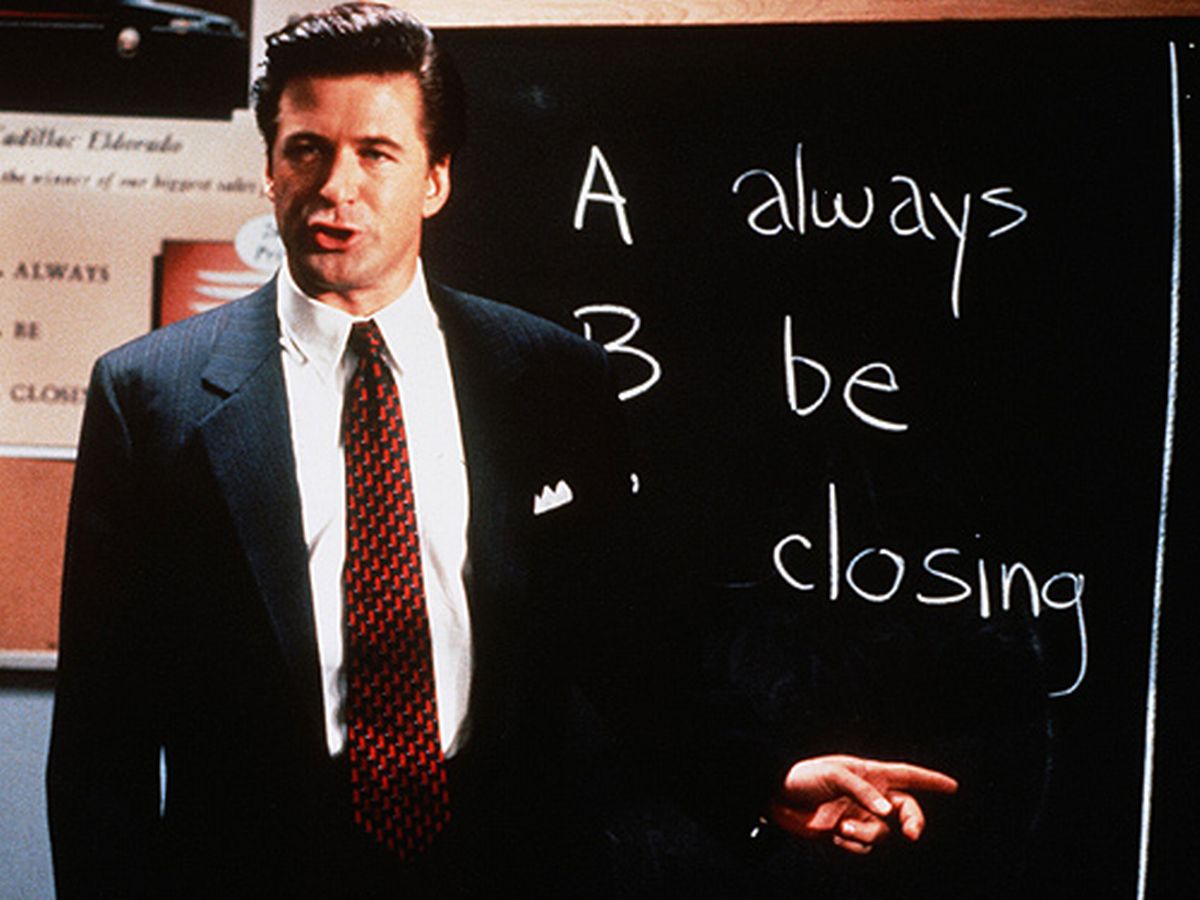

When discussing modern and contemporary American theatre, David Mamet is deservedly part of the conversation. The Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright even did the ol’ stage-to-movie dance by adapting ‘Glengarry Glen Ross’, one of his better works, for James Foley to shoot on film. Examining the lives of four desperate Chicago real estate agents who are ready to go to extreme and even illegal lengths for money, Mamet’s oeuvre first premiered at the National Theatre in London in 1983, followed by an official Broadway opening in 1984 that closed after a whopping 378 performances.

The result is an Oscar-winking timeless drama that brings some marvellous acting chops out of Al Pacino, Jack Lemmon, Alec Baldwin, Alan Arkin, Kevin Spacey, Ed Harris, and Jonathan Price… yes, what a line-up, indeed!

‘GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS’ (1992), ©NEW LINE CINEMA

‘GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS’ (1992), ©NEW LINE CINEMA

‘Dangerous Liaisons’ (1988)

Going back to 18th-century corsets and fancy wigs for a bit, I confess that the era’s decadence and penchant for malice, revenge, and seduction make for great theatre every single time. Christopher Hampton’s ‘Les Liaisons Dangereuses’ 1985 play is no exception, its plot focused on the Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont, two rivals who play cruel games and use sex to humiliate and degrade.

Naturally, such a scandalous affair deserved a sparkling treatment upon transcending into the cinematic dimension. Stephen Frears of ‘The Queen’ (2006) and ‘Dirty Pretty Things’ (2002) fame directs a prodigious ensemble of esteemed actors such as Glenn Close and John Malkovich, turning ‘Dangerous Liaisons’ into one of the ‘80s’ best dramas.

‘DANGEROUS LIAISONS’ (1989), ©WARNER BROS.

‘DANGEROUS LIAISONS’ (1989), ©WARNER BROS.

‘Angels in America’ (2003)

After the titanic success of his political epic play centred on separate but connected individuals in a society struggling with the A.I.D.S. crisis in the ‘80s, Tony Kushner took his two-part Pulitzer and Tony-winning dramatic composition and transformed it into a limited series for television, with Mike Nichols directing. It earned five Golden Globes, of which four went to the cast members—Al Pacino, Meryl Streep, Jeffrey Wright, and Mary-Louise Parker, and it brought a difficult topic back in conversations across America.

While complex and mostly metaphorical in its construction, ‘Angels in America’ is a sincere and gut-wrenching take on homosexuality and AIDS, with major and minor characters designed as supernatural beings—angels and ghosts. Most importantly, the HBO series serves as a crown of glory for a play that was described by John M. Clum as ‘a turning point in the history of gay drama, the history of American drama, and of American literary culture.’

‘ANGELS IN AMERICA’ (2003), ©HBO FILMS

‘ANGELS IN AMERICA’ (2003), ©HBO FILMS

As you can imagine, there are plenty of other titles worth discussing within this creative niche, but the conclusion will always be the same: rare are the plays that work on screen, and even rarer are the writers and directors capable of taking a live performance and turning it into an Oscar-worthy work of cinema.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.