As technology and storytelling evolved, the second half of the twentieth century brought forth a plethora of iconic films that changed the way we see and understand cinema today. Directors of a previous generation delivered their last masterpieces, bowing out gracefully as the new generation emerged with daring new concepts. Young actors we worship today as legends were only just getting started, and from 1961 until 1971, many of their performances made cinematic history.

1961: A New Era Begins

Let us begin with an artistic bang, as it’s ‘Viridiana’ (1961) by Luis Buñuel that marks his return to Spain from a lengthy exile after the 1936-1939 Civil War. The film is notorious for its alleged blasphemy—a crown of thorns tossed into the fire, a cross disguised as a switchblade, and a few other equally controversial elements. It led to the banning of its distribution by the Spanish dictatorship, with support from the Vatican. It’s the parody of ‘the Last Supper’ that drew the clerics’ ire, a medieval feast of fools in which the order of things is inverted. The scene itself is fundamental to forging the film’s merciless black humour.

‘VIRIDIANA’ (1961)

‘VIRIDIANA’ (1961)

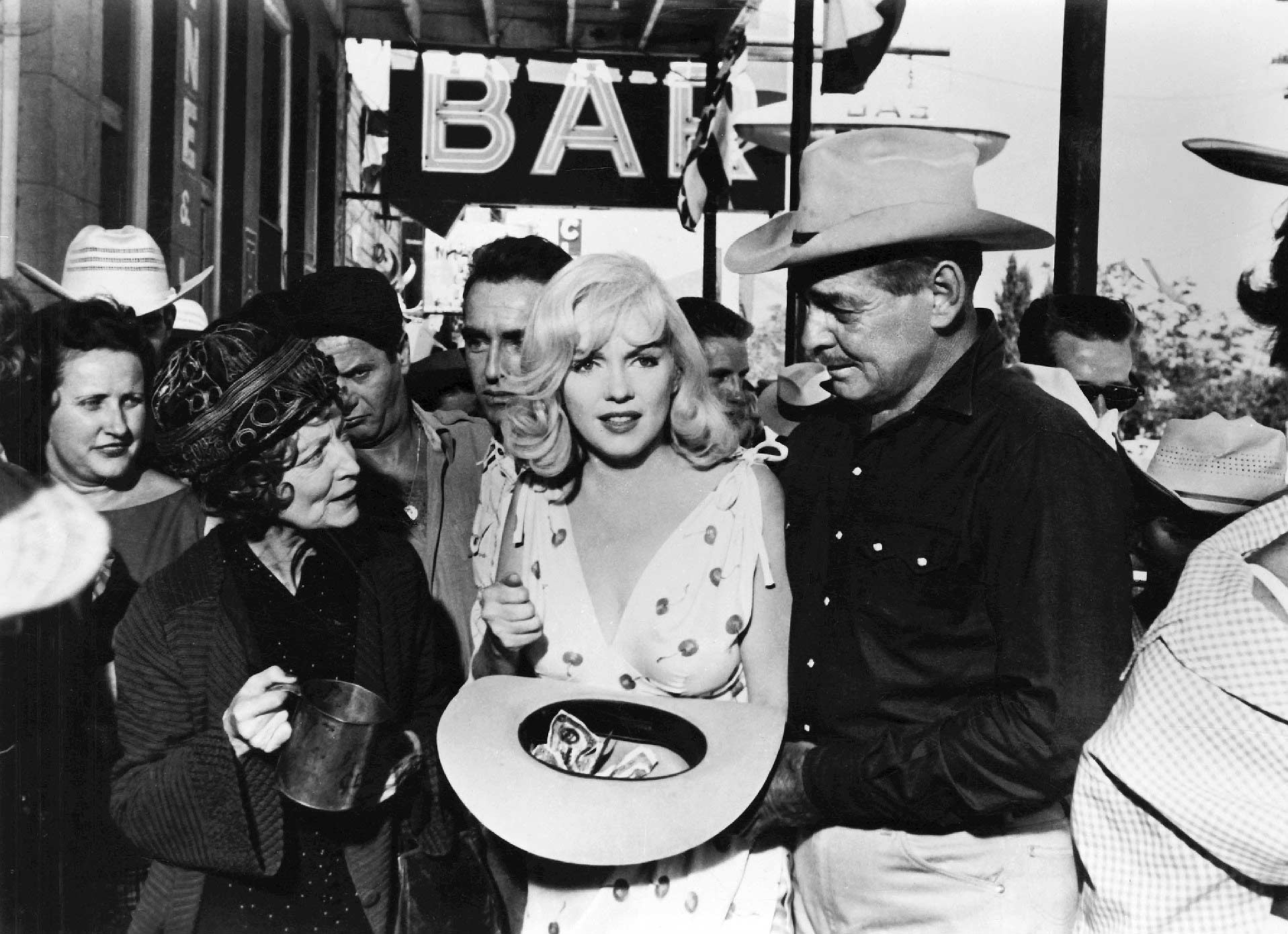

John Huston’s ‘The Misfits’ (1961) is a heart-breaking work of art, showing us Marilyn Monroe like never before. Her Roslyn ends up running into the desolate flatlands, a raw animal howl bursting from her throat and cutting through our souls as the line is blurred between the character and the real woman—it all comes spilling out: the foster homes, the sexual abuse, the divorces, the beatings, the miscarriages, the drugs… Two years later, Ms Monroe would be found dead. I see this particular scene as a foreshadowing of her epitaph, in a way. ‘The Misfits’ is also her last movie and her legacy, a condemnation of the public who kept staring but could never really see how capable an actress she truly was.

‘THE MISFITS’ (1961)

‘THE MISFITS’ (1961)

‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ (1961) by Blake Edwards did not only present a mesmerizing Audrey Hepburn in an iconic role. Holly’s party could very well be the best party scene in movies—made up of easy, loping group shots following people from place to place. We start out small, with Holly’s agent telling stories about her to Paul, her new neighbour. Soon, more people arrive, and it gets crowded. They run out of booze, but a delivery boy brings more. The place becomes packed, wall-to-wall with guests, a couple making out in the shower. This is what people move to New York for, in the end, and it’s why they want out of a party once they’re there: proximity.

‘BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S’ (1961), ©JURROW-SHEPHERD

‘BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S’ (1961), ©JURROW-SHEPHERD

1962: Drama Like Never Before

When it comes to conspiracy thrillers, we cannot discuss proper paranoia without John Frankenheimer’s ‘The Manchurian Candidate’ (1962), starring Frank Sinatra. The circular shot that takes over, eleven minutes into the film, is a surreal 360-degree moment that embodies the visceral fear of mind control. The nightmare scene begins with Sinatra’s Captain Marko seated with other soldiers on a dais at a ladies’ garden society meeting which transforms into huge blow-ups of Mao and Stalin, while a Chinese mind-control expert explains that these American soldiers are test subjects of brainwashing. It is rife with unsettling discontinuities, forcing viewers to alternate between horticulturalists and Communists. This sequence doesn’t just recount mind control. It visualizes it.

‘THE MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE’ (1962), ©M.C. PRODUCTIONS

‘THE MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE’ (1962), ©M.C. PRODUCTIONS

‘Jules and Jim’ (1962) by François Truffaut is a romantic drama of the French New Wave whose ending brings tragedy and transcendence into a whole. Set in the era of the First World War, it chronicles the profound friendship between Oskar Werner’s Jules and Henri Serre’s Jim, both young intellectuals sharing an affection for Jeanne Moreau’s Catherine—the freewheeling beauty that bounces between them. She chooses to marry Jules, yet she doesn’t forsake Jim, either. Jules would rather tolerate their infidelity than lose either of them. This triangle eventually pushes Catherine to kill herself and Jim, forcing Jules to attend their funeral. After he watches their bodies slide into the crematorium furnace, we’d expect him to be most miserable. However, Jules walks out with a spring in his step. Yes, he lost the two people he loved most, but his existential ordeal is now over. He’s entitled to relief.

‘JULES AND JIM’ (1962), ©LES FILMS DU CARROSSE

‘JULES AND JIM’ (1962), ©LES FILMS DU CARROSSE

Despite its light focus on battles and the mass movements of men, David Lean’s ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ (1962) remains a strangely withdrawn film, an epic work of cinema whose lead, T.E. Lawrence (Peter O’Toole), dies in a motorcycle accident before the story properly begins to unfold. Mr Lean is visibly more concerned with the collapse of Lawrence’s project than with anything else. Our final view of Lawrence, for that matter, is also his, as he sits down in the jeep and is driven away, his face disappearing behind the dirty windshield. Ejected from the arena where he had hoped to emerge as extraordinary, Lawrence has become invisible.

‘LAWRENCE OF ARABIA’ (1962), ©HORIZON PICTURES

‘LAWRENCE OF ARABIA’ (1962), ©HORIZON PICTURES

1963: A Year of Epic Cinema

You might remember ‘Cleopatra’ (1963) by Joseph L. Mankiewicz as the dazzling historical film that brought a stupendous Elizabeth Taylor onto the silver screen. Some might recount it’s also where she met her future fifth husband, Richard Burton. But ‘Cleopatra’ made a different kind of history, as Ms Taylor broke $1 million for her performance. Producer Walter Wanger had just lost Joan Collins to scheduling problems for the part, leaving him vulnerable to high demands. Taylor’s contract specified 10% of the film’s gross earnings, racking up a total of $2 million for her acting services alone. She also collected a fee from the use of Todd-AO, an anamorphic widescreen process developed by the late third husband, Michael Todd, which she insisted be used on ‘Cleopatra’.

‘CLEOPATRA’ (1963), ©TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX

‘CLEOPATRA’ (1963), ©TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX

Luchino Visconti’s ‘The Leopard’ (1963) is but one example that showcases the visionary director’s ability to express complex ideas through visual imagery. While it apparently focuses on the patriarchal figure of Prince Fabrizio Salina, eloquently portrayed by Burt Lancaster, the film is more concerned with the changes of Italian society when power is passed from the older generation to the younger. The main representatives of the latter are Salina’s nephew, Tancredi Falconeri (Alain Delon) and Tancredi’s wife-to-be (Claudia Cardinale), whom we see embracing during the party sequence through the film’s final hour. In one astonishing shot, a distant view of them kissing is suddenly invaded by the line of dancers—the contrast between joy and the drabness of conformity gives this scene and the film itself a type of melancholy that is a staple of Visconti’s work.

‘THE LEOPARD’ (1963), ©TITANUS

‘THE LEOPARD’ (1963), ©TITANUS

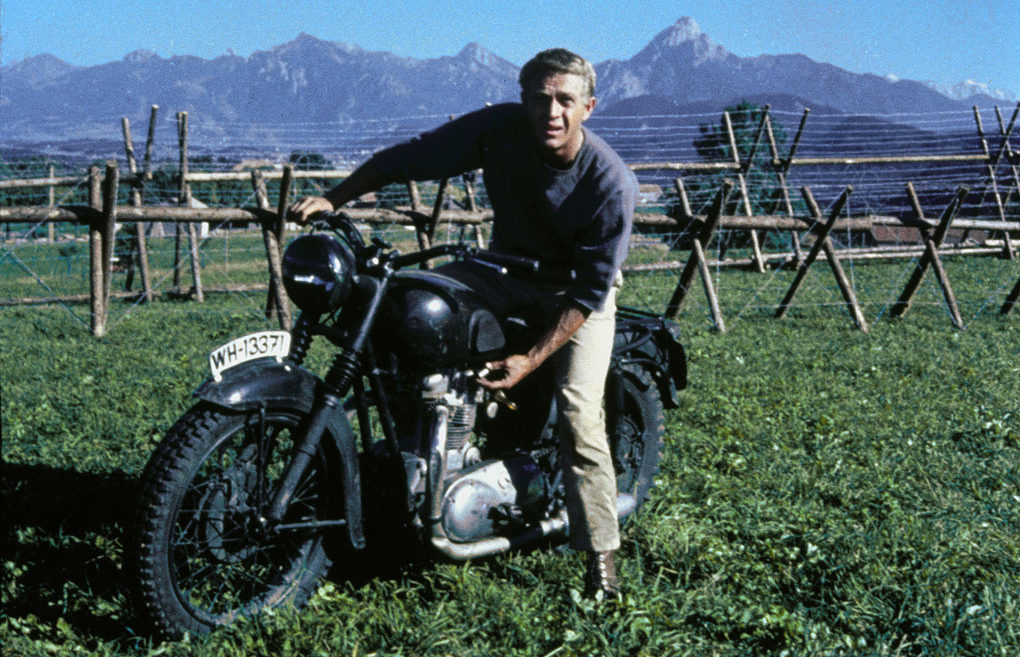

‘The Great Escape’ (1963) by John Sturges is a venerated object of action cinema. Steve McQueen’s Virgil Hilts flees on a motorcycle with Nazis in hot pursuit. After so many minutes of camp prisoners tunnelling toward freedom, the open countryside becomes a beacon of hope. But high barbed fences threaten to thwart Hilts’ narrative of escape—until McQueen himself, the cool stunt daredevil, merges with the P.O.W. escapee and guns the bike’s engine before zooming up over the barrier. I can almost hear the audiences gasping inside a packed movie theatre when this key scene came on. This is the magic of movies, so often linked to the marvel of flight. It’s quite easy to understand why ‘The Great Escape’ is such a great moment in the history of film.

‘THE GREAT ESCAPE’ (1963), ©THE MIRISCH COMPANY

‘THE GREAT ESCAPE’ (1963), ©THE MIRISCH COMPANY

Alfred Hitchcock had already established himself as the master of suspense, yet ‘The Birds’ (1963) took things to a whole new level. The scene outside the schoolhouse is the most memorable. We are in Bodega Bay, and there have already been several attacks by the apparently crazed birds. Tippi Hedren’s Melanie Daniels is waiting for Veronica Cartwright’s Cathy to come out of class—she sits in the playground, elegantly smoking a cigarette with plenty on her mind, plenty enough that she doesn’t even notice the birds landing on the climbing frame behind her. When fluttering finally grips her focus, we’re given a camera swivel from her point of view to find the frame completely covered with birds. We know they will attack. This is a textbook example of building suspense in an apparent narrative dead spot, as all hell is about to break loose.

‘THE BIRDS’ (1963), ©ALFRED J. HITCHCOCK PRODUCTIONS

‘THE BIRDS’ (1963), ©ALFRED J. HITCHCOCK PRODUCTIONS

1965: Rules Change for Women and Action in Film

Russ Meyer’s ‘Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill!’ (1965) brought forth the warrior queen in a format that had been abandoned by other creative mediums. Exotic dancer and martial-artist-turned-actress Tura Satana gained an impressive cult following after her performance as the fierce Varla, a masochist’s wet dream with sharp bangs, cat’s eye make-up, and a stunning hourglass figure wrapped in tight black denim.

While the top-grossing movie of that year portrayed saintly femininity in ‘The Sound of Music’ (1965), Ms Satana was kicking ass and taking names in the California desert, racing cars for kicks and cackling in the faces of men. She pioneered future female-led action flicks such as ‘Kill Bill’ (2003), ‘Alien’ (1979), and ‘The Terminator’ (1984). The way in which Varla, an unstoppable wolverine of a woman, pulls Tommy’s wrists back, presses the heel of her boot to his neck, then snaps his spine with a loud crack, manages to redefine the lead female in action films.

‘FASTER, PUSSYCAT! KILL! KILL!’ (1965), ©EVE PRODUCTIONS

‘FASTER, PUSSYCAT! KILL! KILL!’ (1965), ©EVE PRODUCTIONS

1966: New Western, Dystopia, and Hell’s Angels

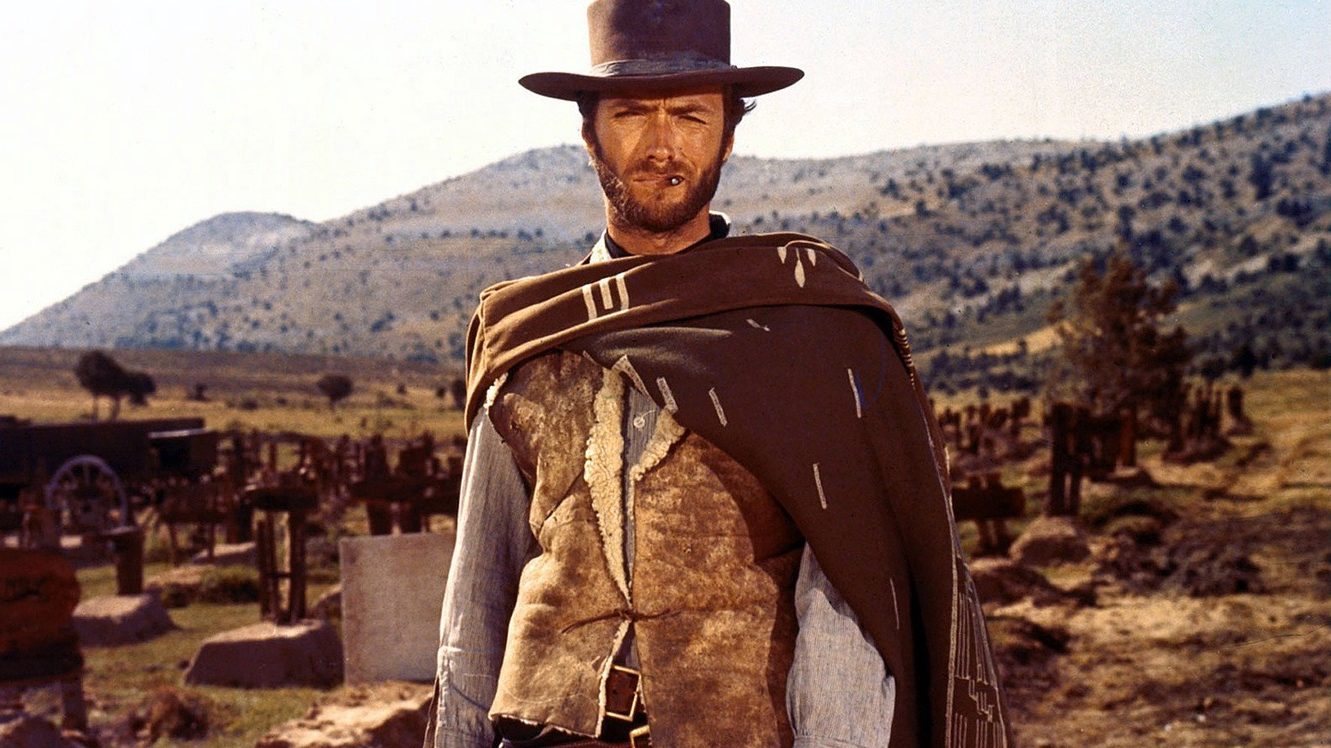

‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’ (1966) by Sergio Leone is a film that insists on two kinds of people existing in the world. The director’s fondness for contrasting two types of shots—close-ups and long shots, finds its conclusion in the grey or blue of the two kinds of soldiers who move toward Eli Wallach’s Tuco and Clint Eastwood’s Blondie from afar. Leone easily turns grey soldiers to blue through a visual instrument of dust, cutting to Blondie and Tuco chained in a prison camp for having worn the wrong disguise in their chase for gold in the middle of a Civil War. Movies were invented for ideas such as this.

‘THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY’ (1966), ©CONSTANTIN FILM

‘THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY’ (1966), ©CONSTANTIN FILM

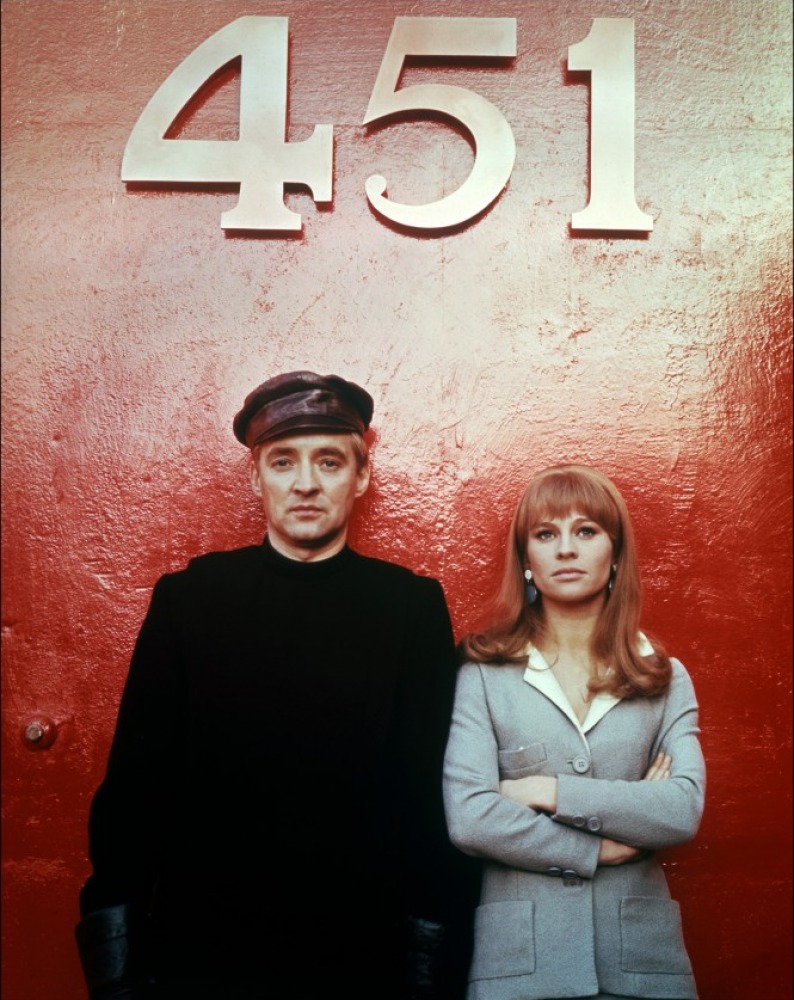

Ray Bradbury’s writing is a paragon of exquisite science fiction. Few were able to transport his works onto the screen—few, among them being François Truffaut’s take on ‘Fahrenheit 451’ (1966). Its credits sequence stands out as a work of its own since Mr Truffaut thematically integrates it into his adaptation of the dystopian novel. Reading is banned in the world of ‘Fahrenheit 451’, and so the titles are spoken, not printed. We listen to the credits like the characters receive the programs they watch on TV. We see a series of photos like the picture-comics they gaze upon instead of reading books or newspapers.

‘FAHRENHEIT 451’ (1966), ©ANGLO ENTERPRISES

‘FAHRENHEIT 451’ (1966), ©ANGLO ENTERPRISES

You’d think the low-budget biker movie craze started with ‘Easy Rider’ (1969), but Roger Corman’s ‘The Wild Angels’ (1966) was the true flame to light that fuse. It’s a quintessential guilty pleasure of that decade, starring Peter Fonda as Heavenly Blues, leader of a California chapter of Hell’s Angels. The transgressive script was penned by Peter Bogdanovich and Monte Hellman, and it features some interesting performances from Diane Ladd (Laura Dern’s mother), Dick Miller, and Nancy Sinatra.

1967: Here’s to You, Mrs Robinson

Aside from Arthur Penn’s ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ (1967) featuring Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty as the notorious outlaws, no other movie has rocked that year’s box-office as firmly as ‘The Graduate’ (1967), directed by Mike Nichols. It gives us a young Dustin Hoffman as Benjamin Braddock, adrift after college and uninterested in a conventional career, who’s lured into an affair by Mrs Robinson, the family friend brilliantly portrayed by Anne Bancroft. Ben gets together with Mrs Robinson’s daughter, Elaine, and soon they fall in love. It breaks down when Elaine discovers his affair with her mother and gets engaged to another man. Even then, Ben refuses to back down as he frantically rushes into the church and basically steals the bride. They board a city bus, headed towards an unknown future. Their lives will never be the same again, and neither will the movies.

‘THE GRADUATE’ (1967), ©LAWRENCE TRUMAN PRODUCTIONS

‘THE GRADUATE’ (1967), ©LAWRENCE TRUMAN PRODUCTIONS

1968: Of Zombies and Apes and MPAA Ratings

A lot happened in 1968. George A. Romero, the father of the cult horror, brought ‘Night of the Living Dead’ to theatres worldwide. It is rightly regarded as a film that made the entire genre enter its modern age, and it also anticipates the trend in more recent horror flicks toward an encouraged use of self-reflexivity. ‘Night of the Living Dead’ also offered one of the most famous lines in the horror department: ‘They’re coming to get you, Barbara!’.

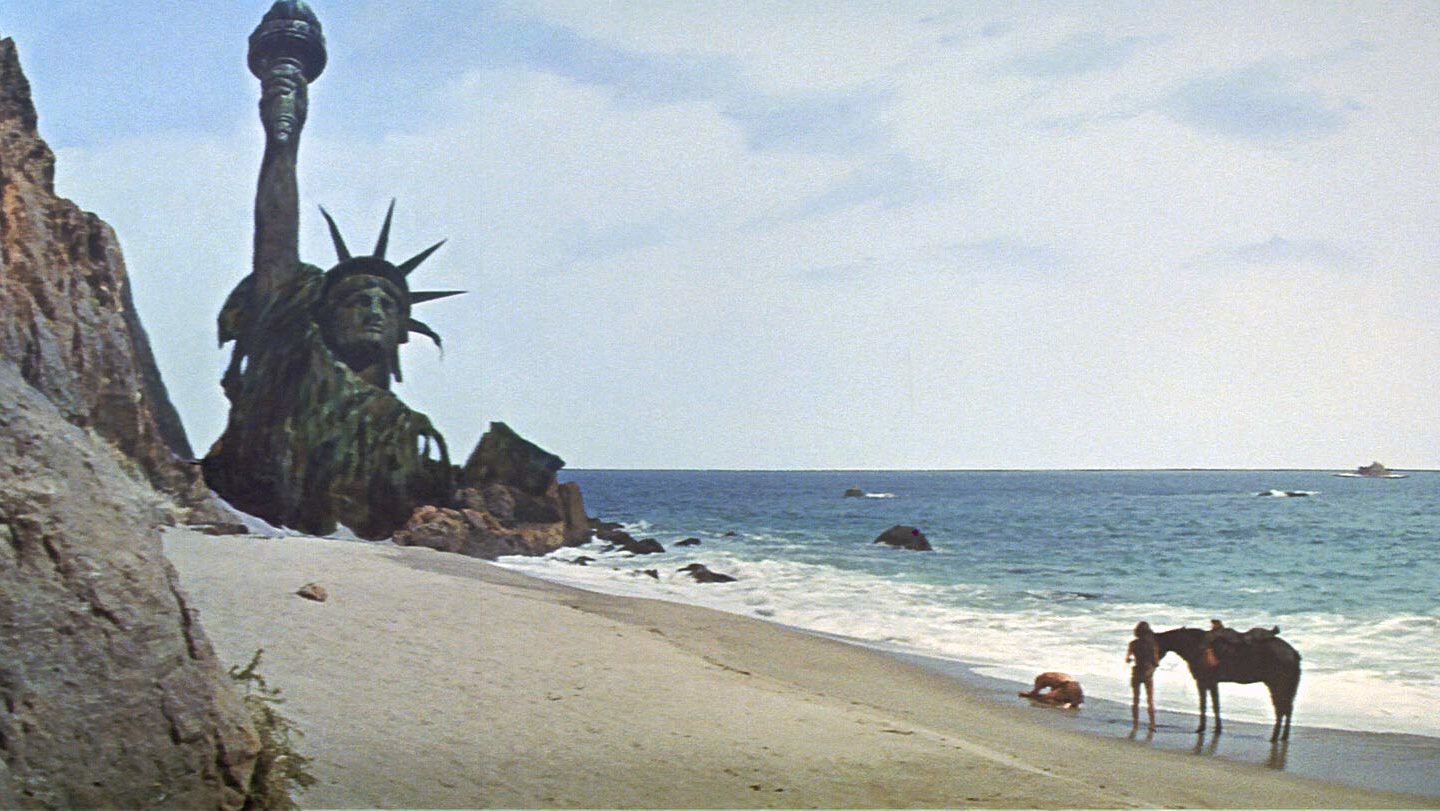

In Franklin J. Schaffner’s ‘Planet of the Apes’ (1968), Charlton Heston is an astronaut stranded on a planet ruled by evolved races of apes. He can never be sure of anything here, and he learns that best in the final scene when he discovers a half-buried Statue of Liberty on a beach and realizes that all this time he was still on Earth. The ending forces viewers to put everything they’ve seen before into a new perspective—a trick that future sci-fi and horror filmmakers will gladly use again.

‘PLANET OF THE APES’ (1968), ©TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX

‘PLANET OF THE APES’ (1968), ©TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX

In November 1968, the Motion Picture Association of America enacted its rating system as a response to the constantly eroding strictures of the old Hollywood Production Code from the 1930s. Despite being looser than its predecessor, the MPAA rating system (G, PG, PG-13, R, and NC-17) was viciously called out by Kirby Dick in his 2006 documentary, ‘This Film Is Not Yet Rated’. His claims focused on the lack of transparency in the board’s decision-making process, along with the fact that it was more hostile to explicit sexual content than extreme violence, stigmatizing gay sex more severely than heterosexual coupling.

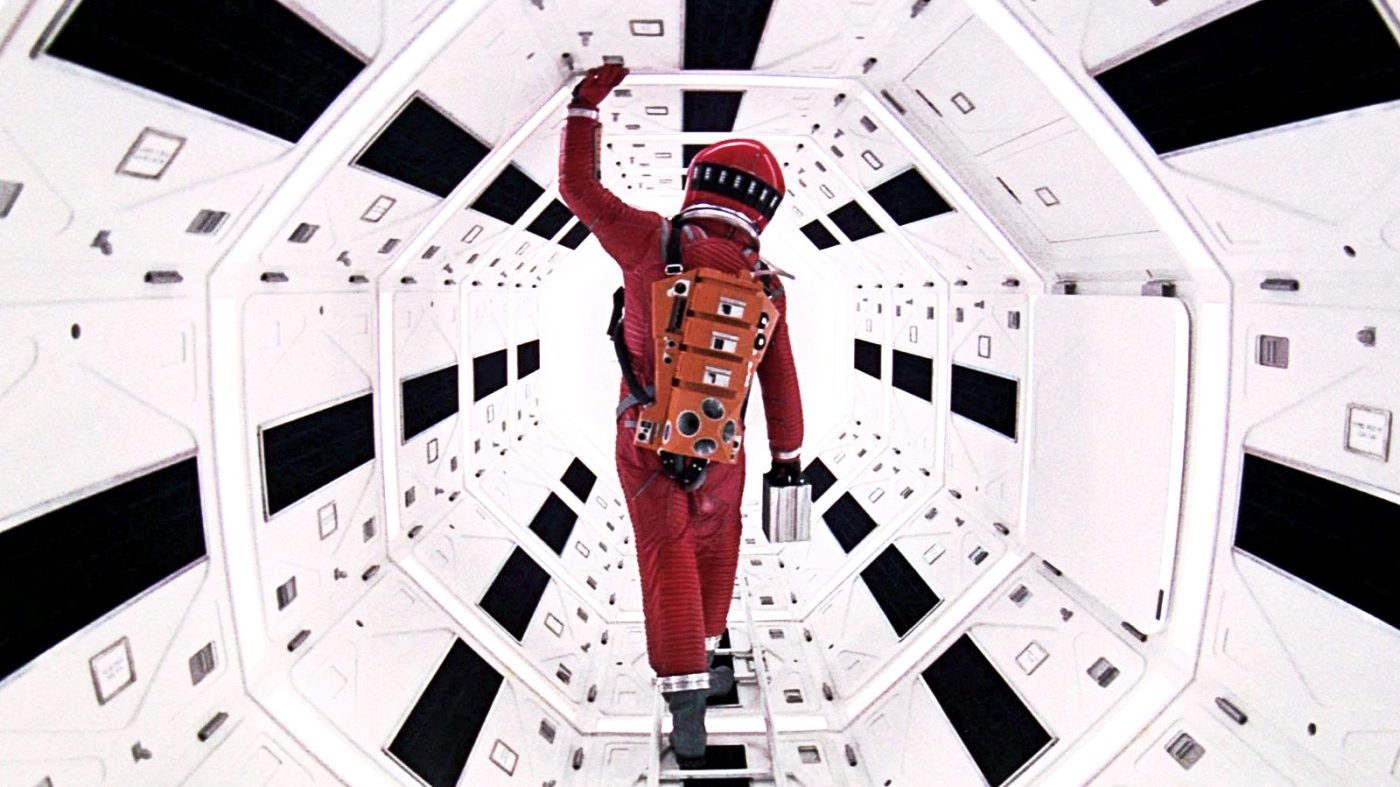

This year also gave us ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (1968) by Stanley Kubrick, based on Arthur C. Clarke’s eponymous sci-fi novel. The premise of this cinematic oeuvre is that some unknown breed of beings has been observing life on Earth from the beginning, only intervening on rare occasions to encourage the evolution of human intelligence. The cut from flying bone to soaring spaceship in the subtitled ‘The Dawn of Man’ first chapter is a legendary cut in modern cinema, making a comment on the possibilities of human evolution that’s as incredibly condensed as a singularity in deep space.

‘2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY’, ©METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER (MGM)

‘2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY’, ©METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER (MGM)

1969: ‘I’m Walkin’ Here!’

Dennis Hopper directed ‘Easy Rider’ (1969), which brings Peter Fonda back as a biker, alongside a young and enthralling Jack Nicholson. The success of this film convinced studios to take a chance on new ideas, new filmmakers, and new audiences, thus reducing the number of screenplay deaths in the fearsome ‘slush pile’.

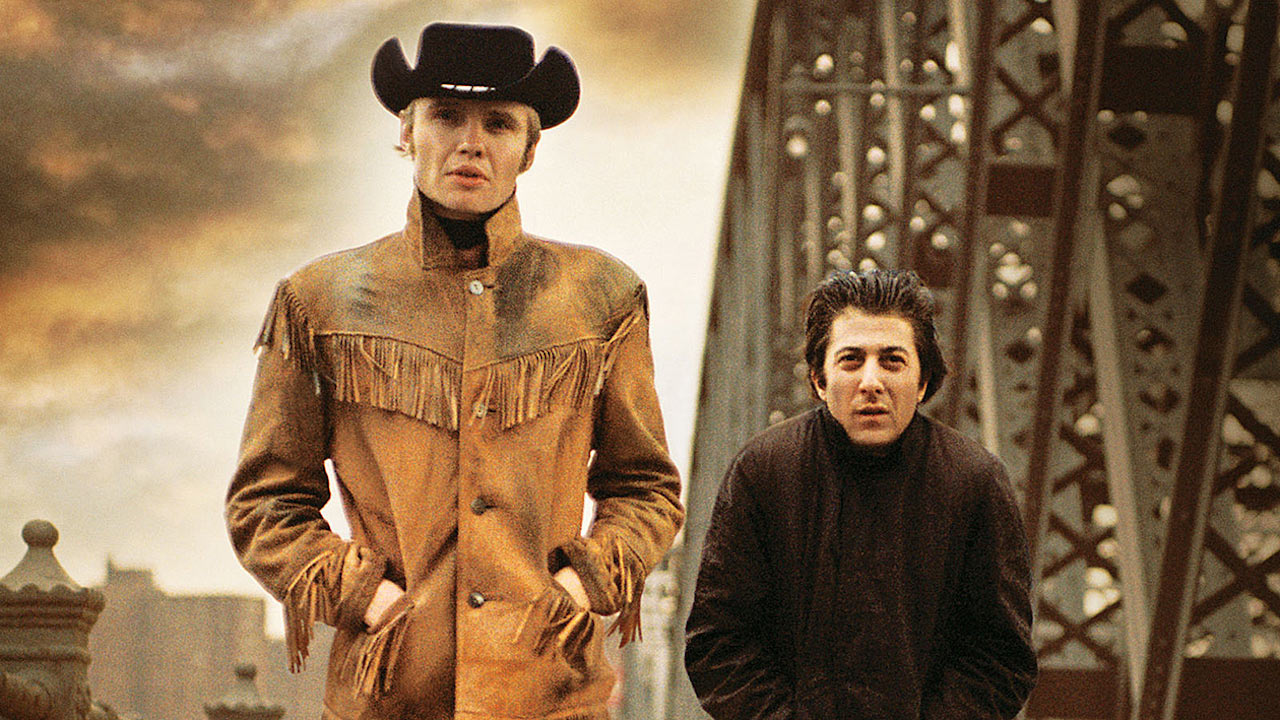

But it was John Schlesinger’s ‘Midnight Cowboy’ (1969), starring Dustin Hoffman and Jon Voight, that made this year all the more memorable through its famous street-crossing line, as the petty criminal of the lower depths demands respect: Hoffman’s Rizzo stumbles onto a Manhattan street just as a taxi nearly runs him over, inciting him to slam his fist on the hood with such force that his cigarette drops from his lips. ‘I’m walkin’ here!’ he shouts, asserting his right to existence.

‘MIDNIGHT COWBOY’ (1969), ©JEROME HELLMAN PRODUCTIONS

‘MIDNIGHT COWBOY’ (1969), ©JEROME HELLMAN PRODUCTIONS

1971: The Rise of Bruce Lee

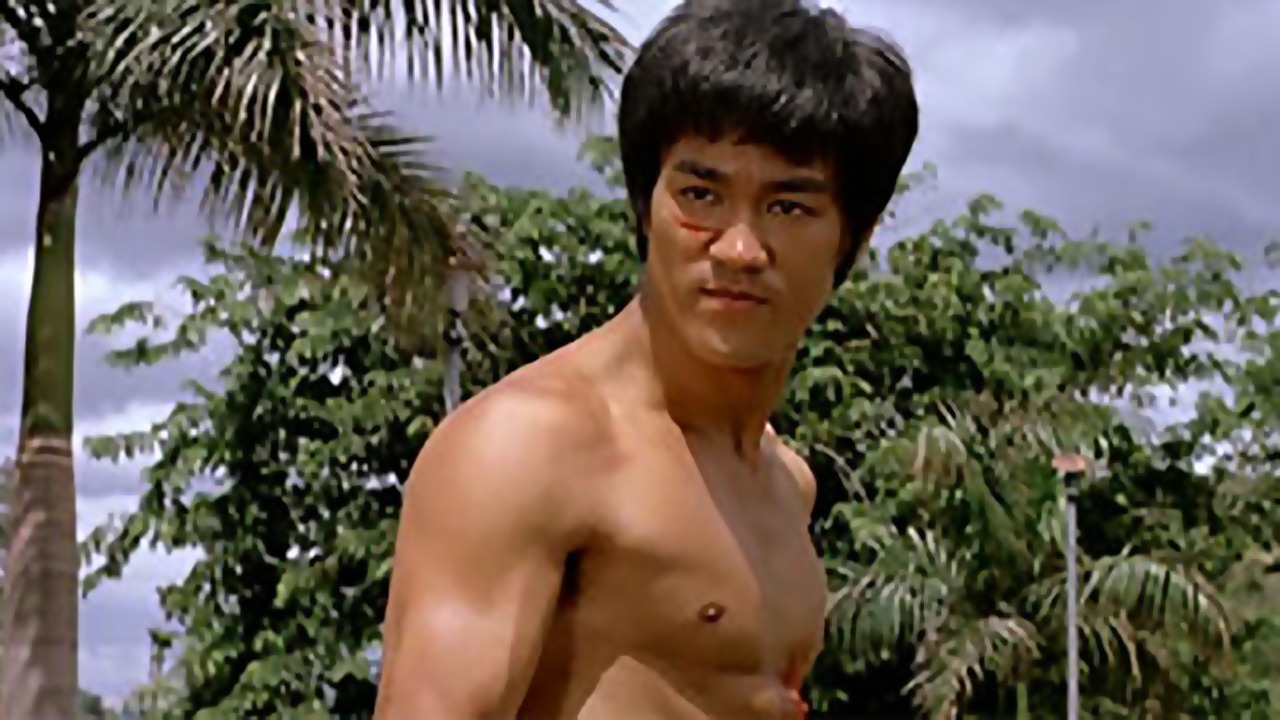

In the United States, Bruce Lee had developed the Jeet Kune Do, ‘art of the intercepting fist’, a combination of Chinese wing chun, Korean taekwondo, and Western boxing and wrestling. Returning to Hong Kong, he put this mastery to good use, making a grand name for himself in Lo Wei’s ‘The Big Boss’ (1971). It is here that the legend of cinema’s dragon was born, as this was the first Chinese martial arts film that crossed over to Western audiences. Like many overnight successes, Mr Lee toiled for years before he became a star of the silver screen. He struggled with Hollywood’s Asian stereotypes, and the last drop was being passed over for a lead role in ‘Kung Fu’, the TV series that had David Carradine as a Shaolin Monk wandering through the American West.

‘THE BIG BOSS’ (1971), ©GOLDEN HARVEST FILMS

‘THE BIG BOSS’ (1971), ©GOLDEN HARVEST FILMS

Mr Lee brokered a deal with Golden Harvest Films in Hong Kong, instead, and the rest became history. Audiences had never seen someone like Bruce Lee before: insolent, charismatic, fast like a panther and effortlessly cool, all-steel physique and whipcrack kicks and punches. He broke the mould and put the world on notice that Asians were more than Hollywood had made them out to be.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.