In my previous discussion regarding this enduring archetype of film and television, I focused most of my attention on the mythological warrior woman—she who transcended from history and myth onto the screen—and the varied attempts made to bring her to life. Today, however, I’m going to talk about pop culture and the gift of the modern Amazon that Hollywood has bestowed upon us.

It is clear that there is an ever-growing trend of powerful women onscreen. This would perhaps hint at a change in society’s attitude toward women, to begin with, if only to the untrained eye. We’ve gone from screaming victims and hapless dancers to ruthless avengers and superheroines in scanty outfits, always ‘packaged’ for maximum commercial consumption. Yet, at the same time, we’ve managed to (accidentally?) create more complex female characters for generations to come. I could hardly call it a feminist victory—in certain aspects, Western society still has a way to go, but it is best to enjoy the full half of the glass.

‘THE AVENGERS’ (1961-1969), ©ASSOCIATED BRITISH CORPORATION

‘THE AVENGERS’ (1961-1969), ©ASSOCIATED BRITISH CORPORATION

The Land Before Time

During the ‘60s, there was a massive influx of testosterone-powered tales of great adventures whose heroes exhilarated their audiences by killing ferocious animals with their slick revolvers before they found themselves speechless in front of a full-breasted lady that sort of… ‘didn’t belong’. From thereon, almost accidentally, the ‘wild heroine’ evolved.

Filmmakers opted for exotic or prehistoric landscapes in which to challenge their female protagonists, usually in eras when clothing was scarce, which was fine for exposing their gorgeously chiselled curves. Almost always, the leading lady was a blonde, a ‘white goddess of the jungle’—just one example of the many racial tones that consistently plagued productions of that era, as ‘white’ was perceived as code for ‘good’ and ‘black’ was considered ‘evil’.

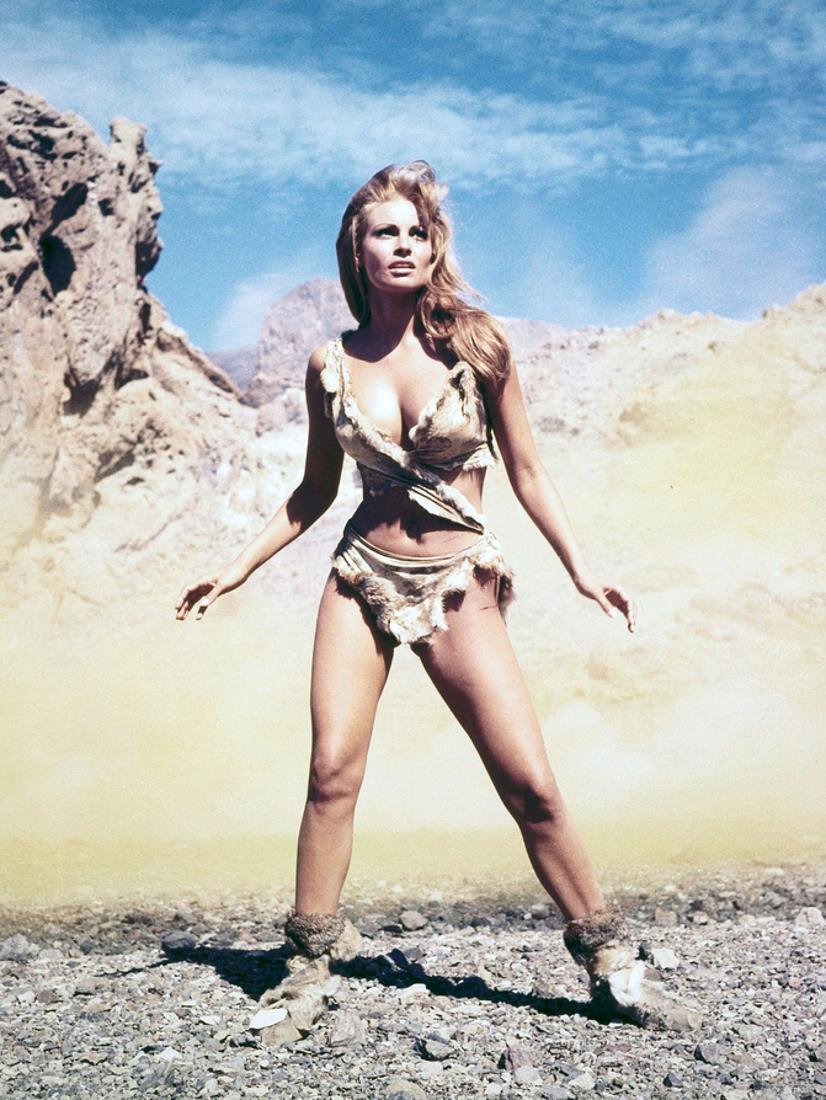

The most memorable prehistoric warrior queen of that time is Raquel Welch as Loana in ‘One Million Years B.C.’ (1966). While it elevated her to international sex-symbol status, the film itself was a remake of a 1940 original that starred Carole Landis and Victor Mature, and most of its box-office power stemmed from the nearly gratuitous exploitation of Welch’s stunning figure—her character sports fur bikinis, heroically rescues the male protagonist Tumak, and has heated fight scenes with equally enticing cavewomen, dancing dangerously on the edge of volcanic eroticism.

Loana inadvertently falls for Tumak and leaves her beloved tribe and known world to trek across a dangerous desert beside him not as a companion but as an equal. She faces dangers and fights dinosaurs and members of the rock tribe, yet she doesn’t alienate the male audience with her warrior nature. Fundamentally, Loana is still the nurturing and composed influence of the story, smoothly sliding into the traditional and universally accepted slot usually reserved for women in film and literature.

‘ONE MILLION YEARS B.C.’ (1966), ©HAMMER FILMS

‘ONE MILLION YEARS B.C.’ (1966), ©HAMMER FILMS

Before Welch, former model Irish McCalla had made her share of waves as a ‘wild presence’, donning leopard skins and blowing her signature buffalo horn in ‘Sheena: Queen of the Jungle’ (1955-1957). A cause for numerous wet dreams among mid-century teens, this particular depiction bears a striking resemblance to the Venus of Laussel, a Palaeolithic deity dating back 20,000 years, as identified by David Broad in his article for ‘Studies in Popular Culture’ of 1997. Like many of her warrior counterparts in television, Sheena was a product of the comic book realm, created as a female rival to Tarzan by Will Eisner and S.M. Iger.

She, too, was abandoned and raised in the jungle. She, too, displayed the perfect, powerful physical form. She, too, had a flawless sense of right and wrong. Alas, Sheena’s popularity was doomed to eventually fade, given that period’s repressive Eisenhower-McCarthy climate when social emphasis became laser-pointed on the nuclear family. The woman needed to be pushed out of the workforce that had previously welcomed her during WWII and sent back into the ‘loyal housewife’ or ‘brainless bombshell’ moulds, instead.

But while it lasted, ‘Sheena: Queen of the Jungle’ presented an indisputable appeal through Ms McCalla, a pinup dame that reminded Hollywood brass and network viewers of the Marilyn Monroe and Jayne Mansfield type that had already blown up on the silver screen. As a character, she was notedly different: innocent yet strong-willed, a fighter, and a nurturer.

‘SHEENA: QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE’ (1955-1957), ©NASSOUR STUDIOS INC.

‘SHEENA: QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE’ (1955-1957), ©NASSOUR STUDIOS INC.

Other notable examples of the savage woman warrior from lost ages include ‘Jungle Girl’ (1941), a fifteen-part serial based on Edgar Rice Burroughs’ novel that follows France Gifford’s Nyoka becoming a reckoning force of wilderness; ‘Saga of the Viking Women and their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent’ (1957) by Roger Corman, which sees traditional roles reversed with men kept in bondage as the women pursue their rescue; and a ton of otherwise mediocre titles that include the word ‘Amazon’ solely as an excuse to use as little costume material as possible.

The Warrior Ladies of ‘Conan the Barbarian’

The ‘70s had been brewing a comeback of the warrior queen for quite a while before Robert E. Howard’s Conan hit the big screens. The three movies that ultimately secured Arnold Schwarzenegger’s career also brought forth some phenomenally badass women, heavily influenced by ‘Wonder Woman’ (1975-1979) and ‘The Bionic Woman’ (1976-1978). At the time, there was also a steady fandom growing around the French comics of ‘Metal Hurlant’ and their English sister ‘Heavy Metal’, along with the smashing success of the ‘Dungeons & Dragons’ roleplaying game. It’s what we, today, might call a perfect storm.

‘CONAN THE BARBARIAN’ (1982), ©UNIVERSAL PICTURES

‘CONAN THE BARBARIAN’ (1982), ©UNIVERSAL PICTURES

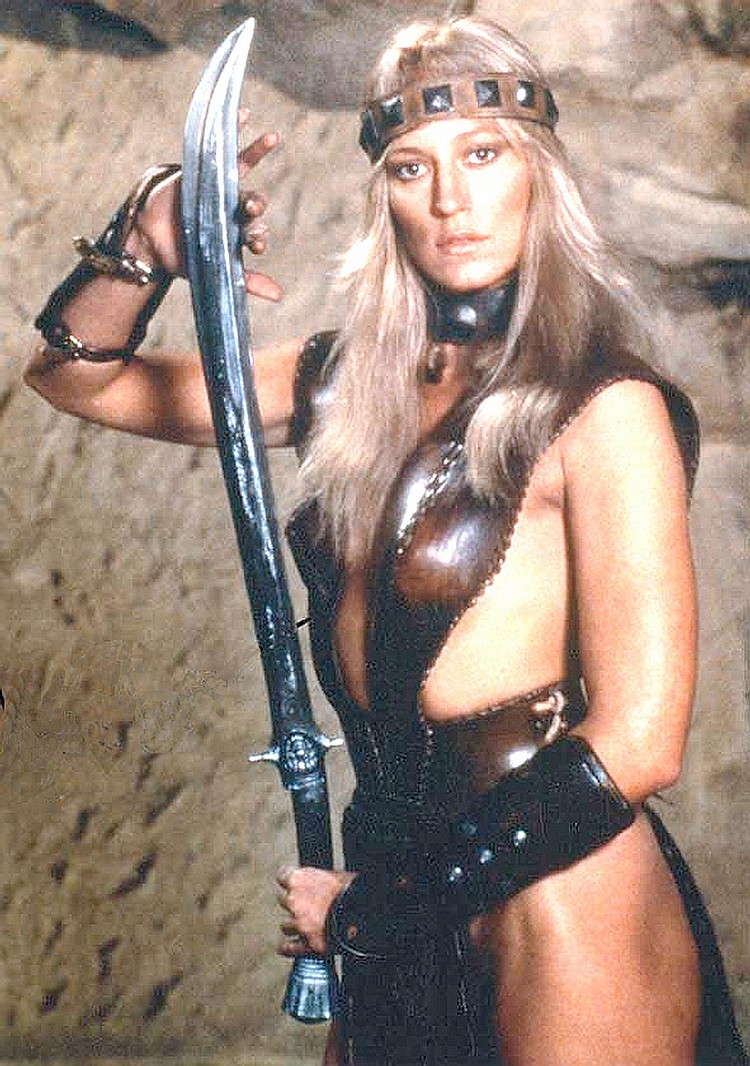

Valeria of ‘Conan the Barbarian’ (1982) was the first to combine all of the above elements, epitomizing the Viking ideal of power and beauty. Portrayed by Sandahl Bergman, she was tall, blonde, gorgeous, and a worthy match for Conan on every level. She equalled him in thievery and in lovemaking, ultimately winning his eternal devotion when she sacrificed herself to save him from James Earl Jones’s villain Thulsa Doom.

‘CONAN THE DESTROYER’ (1984), ©UNIVERSAL PICTURES

‘CONAN THE DESTROYER’ (1984), ©UNIVERSAL PICTURES

In ‘Conan the Destroyer’ (1984), the female protagonists are decidedly strong-willed. Queen Tamaris, played by Sarah Douglas, is ruthless in her desire to awake the god Dagoth and rule beside him, while teen princess Jehnna, embodied by Olivia D’Abo, is spoiled but wise to follow her instincts since Conan’s judgment is still clouded by the loss of Valeria. My absolute favourite is Grace Jones’s Zula, an incarnation of the model’s performance art—gorgeous, gender-bending, primal, and fierce as a panther.

The third film of the Conan series, ‘Red Sonja’ (1985), was a painful stretch and a box-office flop. It ended further adaptations that had been originally planned for Schwarzenegger’s iconic character even though it didn’t feature him onscreen. While still based on Howard’s stories, the film brought forth Brigitte Nielsen as the dominating female protagonist and alluring fantasy warrior. Unfortunately, the lack of acting chops and irritating attempts at annoying relief tanked the whole franchise. Fortunately, there’s a reboot on the way, penned by Joey Soloway and Tasha Huo, and featuring Hannah John-Kamen of ‘Ant Man and the Wasp’ (2018) and ‘Brave New World’ (2020) fame as Red Sonja.

‘RED SONJA’ (1985), ©DINO DE LAURENTIIS COMPANY

‘RED SONJA’ (1985), ©DINO DE LAURENTIIS COMPANY

The Honourable Shieldmaiden

Most of the high fantasy genre is still male dominated. No surprise there, considering oeuvres such as the ‘Lord of the Rings’ trilogy by J.R.R. Tolkien, whose Middle-Earth realm is fought over and controlled by the men of the species—human, elf, hobbit, and orc alike. We’ve got Aragorn, son of Arathorn and key protagonist. We’ve got Frodo, Sam, Pippin and Merry. We’ve got Legolas and Gimli. Gandalf and Saruman. We’ve got Elrond and Eomer and, well, you get the picture. Sure, let’s give Arwen a nod here, why not? After all, Peter Jackson did do a grand job of recalibrating Tolkien’s handful of female characters for a generation of viewers that are better accustomed to women in combat roles.

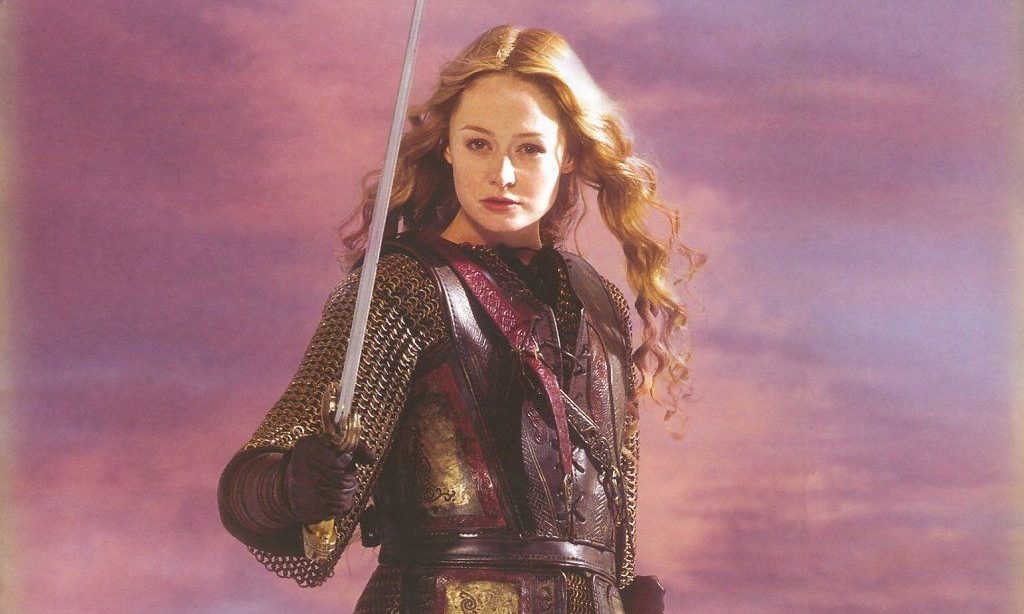

But the true warrior woman exception of ‘The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers’ (2002) and ‘The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King’ (2003) is the incomparable Eowyn, niece of King Theoden, superbly portrayed by Miranda Otto. Demonstrating her expertise with bladed weapons early on, she comes across as an aggressive fighter unfortunately still repressed by the king and by the traditional role that she’s expected to fit into—despite death itself knocking on Rohan’s battered gates. By the climax of the trilogy’s third part, however, Eowyn has slipped into a suit of armour and joined the armies of men against the evil of Sauron. She has fought valiantly and nearly died to defend humanity’s ideals. She has resisted darkness and despair, and she has held her king in his dying moments.

‘THE LORD OF THE RINGS: RETURN OF THE KING’ (2003), ©NEW LINE CINEMA

‘THE LORD OF THE RINGS: RETURN OF THE KING’ (2003), ©NEW LINE CINEMA

Xena and Her Conscience, Gabrielle

Originally designed as a companion to ‘Hercules: The Legendary Journeys’ (1995-1999), ‘Xena: Warrior Princess’ (1995-2001) went on to outgrow its brother and became a turning point in the history of television due to its exquisite development of the warrior woman archetype within that epoch and its sensible approach to depicting female protagonists, in general—as opposed to the usually objectified babes I mentioned earlier. What I found most extraordinary was the depth with which fans (most of them women) connected with the show. It was an intimate relationship that led to numerous discussion boards dissecting each episode, proving that Xena’s supporters weren’t just passive consumers but interactive viewers who later shaped and steered the show.

Once one begins to peel away at the many layers that made Sam Raimi’s work such a success, one can’t help but notice the beautiful dynamic between Lucy Lawless’ spicy Xena and Renee O’Connor’s more down-to-earth Gabrielle. The warrior and the maid. The sword and the shield. The fighter and the peacemaker. Through the entire series, Gabrielle becomes Xena’s focal point and recipient of all her affection and loyalty, leading to the protagonists splendidly complementing each other. The former is more ‘traditionally feminine’ and the latter’s conscience, a counterweight to Xena’s cruel instincts that once defined her violent past. In this show’s universe, the warrior queen carries herself with two equally beautiful faces: Xena and Gabrielle.

‘XENA: WARRIOR PRINCESS’ (1995-2001), ©MCA TELEVISION

‘XENA: WARRIOR PRINCESS’ (1995-2001), ©MCA TELEVISION

The Monster Killer

For a long time in horror films, there was a recurring pattern of the woman conceptualized more as victim than as hunter, which is why the ‘90s and the ‘00s rose in rebellion with tales of modern female protagonists who turned the trope inside out and started fighting back against the terrible monsters. See Milla Jovovich in ‘Resident Evil’ (2002), for example, who reacts with instinctive power and magnificent combat techniques when zombies and mutant beasts come to kill her.

The Gothic heroines of the past are gone. In their place come enticing femme fatales who wield stakes and blades and machine guns with remarkable ease. See Kate Beckinsale in ‘Underworld’ (2003), in which she takes on the lead not only as a woman but as a vampire—a monster hunting monsters. Clearly, the warrior queen at the turn of the new century is infinitely more complex and dons a darker side.

‘UNDERWORLD’ (2003), ©LAKESHORE ENTERTAINMENT

‘UNDERWORLD’ (2003), ©LAKESHORE ENTERTAINMENT

This new action figure was skilfully defined early on through ‘Buffy the Vampire Slayer’ (1997-2003), winner of two Primetime Emmys and the favourite show of several generations. Joss Whedon’s cult classic wasn’t expected to do as well as it did, ultimately spawning a spinoff for David Boreanaz in the process. Truth be told, the series is one of the most ambitious feats of television that virtually reshaped parts of the creative process behind future similar monster-slashing projects. It did a spectacular job with character development, too.

The monsters were never the dominant aspect of ‘Buffy the Vampire Slayer’. They served as bloody and exciting décor for a story whose heroine tried to wade through life as a young adult, as a misfit, as a daughter and as a friend, struggling with the common issues that made Sarah Michelle Gellar’s character so relatable and beloved by most—love, life, death, sexual experimentation, and profound self-identity crises. At times campy and worn out, the show did bring forth a protagonist that became a celebrated milestone in TV history.

‘BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER’ (1997-2003), ©MUTANT ENEMY

‘BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER’ (1997-2003), ©MUTANT ENEMY

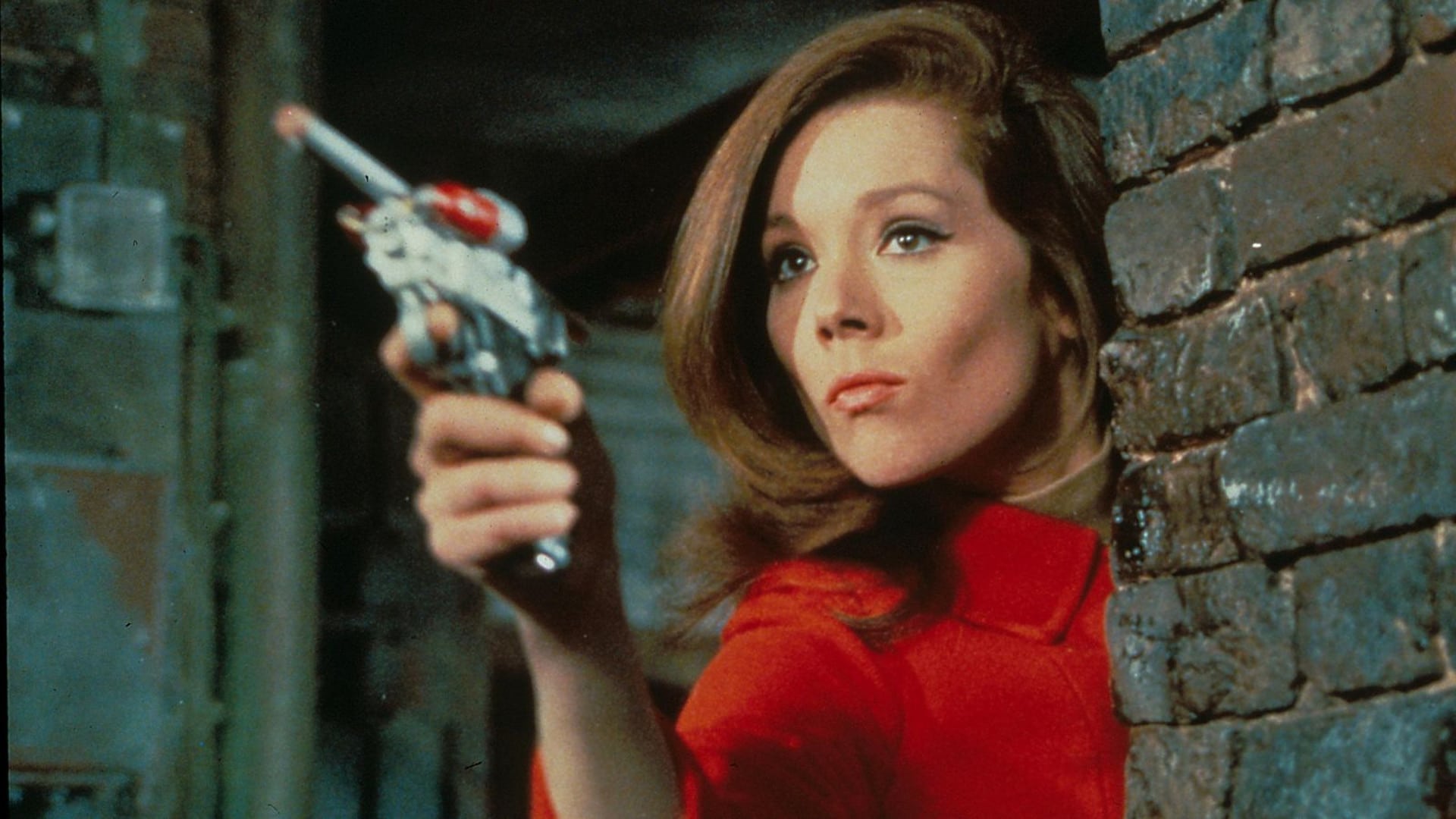

Not forgetting Lori Petty’s prolific ‘Tank Girl’ (1995), Diana Rigg’s statuesque, raspy-voiced Emma Peel in ‘The Avengers’ (1961-1969), Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley in ‘Alien’ (1979), Jennifer Garner’s Sidney in ‘Alias’ (2001-2006), nor Uma Thurman’s Bride in ‘Kill Bill: Vol. 1’ (2003), among many others, when addressing the warrior queens of pop culture, it’s delightfully plain to see that the film and television industry have come a long way. Sure, there’s still just as much ahead as we struggle to forge unique and original female characters, but the warrior woman has not only become more popular in recent decades… She has become downright indispensable.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.