As old as our collective recorded history, the warrior woman’s archetype has found a place in almost every medium. From the ancient myths of the Greek Amazons depicted on ceramic amphoras and frescoes to the literary tales of maidens picking up swords to fight against evil, this particular brand of heroine eventually emerged onto the screens in the 20th century.

We didn’t simply dream up the warrior queen. Around 1200BC, Fu Hao, one of the sixty wives of Wu Ding, a Shang Dynasty emperor, broke with tradition and led military campaigns, ultimately remembered as the most powerful leader of her time. East of the Caspian Sea, Tomyris ruled over a confederation of nomadic tribes and waged a vengeful war against Cyrus the Great.

‘THE LEGEND OF TOMIRIS’ (2019), ©KAZAKKHFILM STUDIOS

‘THE LEGEND OF TOMIRIS’ (2019), ©KAZAKKHFILM STUDIOS

Herodotus wrote of Artemisia I, the Queen of Halicarnassus who fought beside the Persian king Xerxes I during his empire’s second invasion of Greece. There was the remarkable Boudicca of the Celtic Iceni tribe, and there was Triệu Thị Trinh, better known as Lady Triệu, who briefly freed her Vietnam homeland from Chinese rule in the 3rd century. Our history is filled with fantastic women.

There is nothing sexier than a woman with a weapon in her hand and justice on her side. Hollywood was more than happy to take the warrior queen archetype and unravel it into a plethora of motifs that would later go on to inspire the ‘modern Amazon’. Today, I’ll begin my study with the mythological aspect first, since it has been a treasure trove of story ideas for screens both big and small.

PORTRAIT OF LADY TRIEU

PORTRAIT OF LADY TRIEU

A Patron Saint of France

Joan of Arc was the first true woman warrior to be dealt with by the cinema and the only one to be thus honoured for the first sixty years of film history or so. If you’re wondering why that was the case, the answer will strike you as deceptively simple. Joan was canonized by the Catholic Church more than five hundred years after the same Church burned her at the stake as a heretic. She was a safe bet for filmmakers of the early 20th century.

Maria Falconetti played the sanctified heroine in ‘The Passion of Joan of Arc’ (1928), led by prestigious Danish director Carl Dreyer. She was followed by Ingrid Bergman in Victor Fleming’s ‘Joan of Arc’ (1948) and later in Roberto Rossellini’s musical version ‘Joan of Arc at the Stake’ (1954). Jean Seberg took her on in ‘Saint Joan’ (1957), directed by Otto Preminger—which was Graham Greene’s more realistic take on the eponymous theatre play penned by George Bernard Shaw.

‘The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc’ (1999), Luc Besson’s interpretation of the gender-bending Maid of Orléans, stood out for me. It is a modern and decidedly unconventional treatment of the fabled Joan, which sees Milla Jovovich ‘in physical dimensions and in sexual intensity far removed from any of the Joans before her’, as Dominique Mainon and James Ursini describe her in ‘Modern Amazons: Warrior Women on Screen’.

‘THE MESSENGER: THE STORY OF JOAN OF ARC’ (1999), ©COLUMBIA PICTURES/GAUMONT

‘THE MESSENGER: THE STORY OF JOAN OF ARC’ (1999), ©COLUMBIA PICTURES/GAUMONT

The Ancient Greek Amazons

For a long time, the Amazons were believed to be purely fictional, though recent archaeological discoveries place them in the northern and eastern regions of the Mediterranean. They were, in fact, identified as Scythians, and they fought, rode horses, and used bows and arrows just like the men. The Amazons were described as the archenemies of the Greeks. In fact, all Greek champions and heroes of legend, from Theseus to Achilles and Hercules, had to prove themselves by fighting powerful warrior queens—Hippolyta, Antiope, and Thessalia being listed among them.

DC Comics took the Amazon out of the myth and into their printed pages when they created Wonder Woman, one of their most popular characters and an inspiration to little girls and young women everywhere. Diana Prince made her way onto the small screen first in the ‘Wonder Woman’ (1975-1979) TV series, starring Lynda Carter and Lyle Waggoner. Much later, the heroine was brought back by Patty Jenkins with ‘Wonder Woman’ (2017) and ‘Wonder Woman 1984’ (2020), which saw Gal Gadot take over as the revered female warrior and Chris Pine as her beloved, Steve Trevor.

‘WONDER WOMAN’ (2017), ©WARNER BROS.

‘WONDER WOMAN’ (2017), ©WARNER BROS.

Boudicca and Guinevere

In English folklore, fiction and history often intertwined, giving us remarkable ladies such as Boudicca. Alas, the Iceni queen never really found a home on the silver screen, though some have tried to bring her story to life. Don Chaffey’s ‘The Viking Queen’ (1967) was a tepid adaptation, at best, and Bill Anderson’s ‘Warrior Queen’ (2003) failed to take off. Despite the honourable intentions, the fierce Boudicca will have to wait a bit longer for a filmmaker to come along and inscribe her name onto the gilded walls of pop culture.

In the meantime, Guinevere of King Arthur fame was transformed into a fierce warrior for ‘King Arthur’ (2004), Antoine Fuqua’s bold take on the English legend. Unlike previous works of literature, Keira Knightley’s Guinevere picks up a bow and arrow and fights the Romans as fiercely as every other man.

‘WARRIOR QUEEN’ (2003), ©MEDIA PRO PICTURES

‘WARRIOR QUEEN’ (2003), ©MEDIA PRO PICTURES

The Rise of Hua Mulan

Fu Hao wasn’t the only warrior woman to stand out in China, but Hua Mulan was the more popular one worldwide. The Ballad of Mulan, a folk song dating from the Han dynasty, is among the better-known written records of the fabled heroine who took her father’s place in the army in order to serve her country and bring honour to her family. Walt Disney Animation Studios picked her up in the animated ‘Mulan’ (1998) as part of an effort to revamp their princess model and move away from the damsel-in-distress tropes that had begun to alienate audiences of those years. Jingle Ma and Wei Dong tried their hand at a live action version with ‘Mulan: Rise of a Warrior’ (2009), later followed by Disney’s own ‘Mulan’ (2020) with Niki Caro as director.

Much like Boudicca, however, it seems like this story has yet to meet a filmmaker whose creative vision might do her justice. I, for one, have found a better variant of the Chinese warrior woman archetype in epic martial arts films such as Ang Lee’s ‘Hidden Dragon, Crouching Tiger’ (2000) and Zhang Yimou’s ‘House of Flying Daggers’ (2004).

‘MULAN’ (1998), ©WALT DISNEY ANIMATION STUDIOS

‘MULAN’ (1998), ©WALT DISNEY ANIMATION STUDIOS

Italian Folklore’s Warrior Maiden

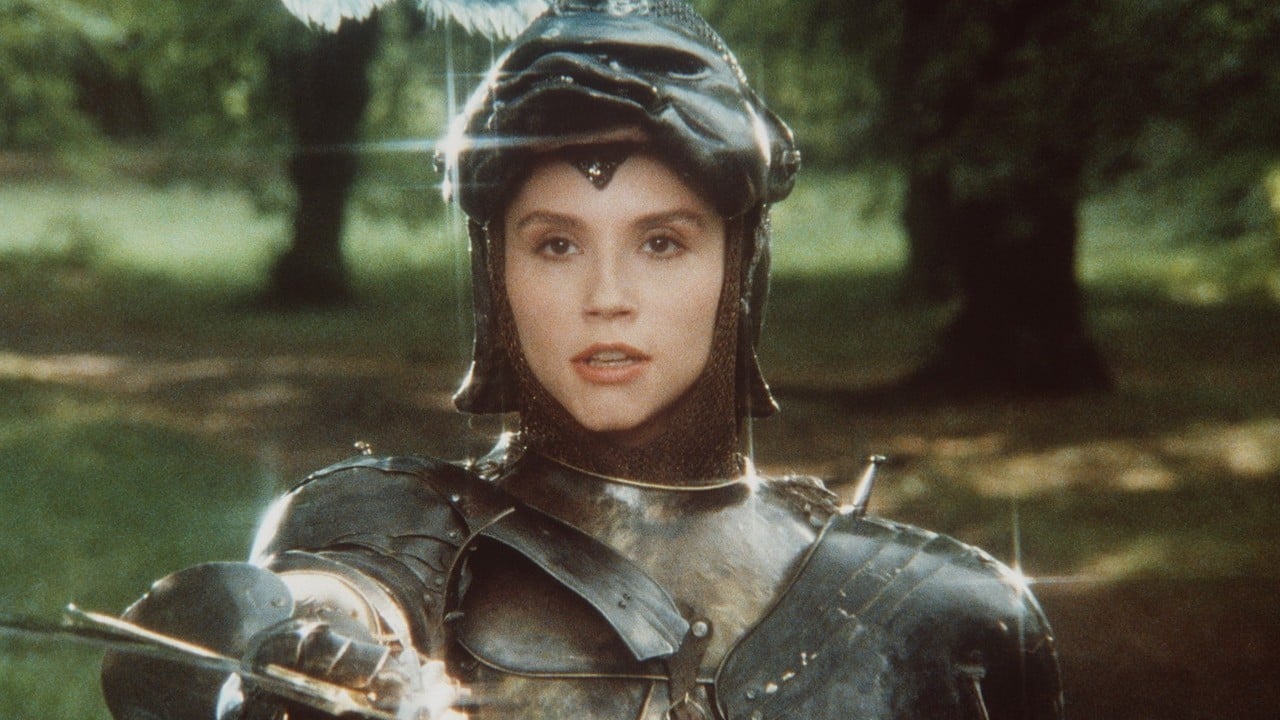

Fantaghirò found surprising success in the ‘90s thanks to Lamberto Bava and Gianni Romoli, who drew inspiration from Italo Calvino’s ‘Italian Folktales’ as they brought forth a series of television films dedicated to the brave princess-turned-warrior.

Going against the traditions and customs of her era, Fantaghirò was literate, adventurous, and rebellious, eventually picking up a sword to save her father’s kingdom. Starring Alessandra Martines, Kim Rossi Stuart, and Brigitte Nielsen, and featuring a music score composed by Amedeo Minghi, ‘Fantaghirò’ (1991-1996) drew inspiration from other cult darlings of the high fantasy genre such as ‘Legend’ (1985) by Ridley Scott, ‘Ladyhawke’ (1985) by Richard Donner, and ‘Willow’ (1988) by Ron Howard.

‘FANTAGHIRO’ (1991), ©RETEITALIA/RAI

‘FANTAGHIRO’ (1991), ©RETEITALIA/RAI

The Viking Valkyrie

In the Norse tradition, the shieldmaiden Brunhilde is better known as a Valkyrie, present in the Völsunga saga and the Poetic Edda. Most notably, she is central to ‘The Song of the Nibelungs’, one of the first written poems drawn from Germanic oral traditions. Instrumental in the death of the hero Siegfried after he deceived her into marrying Gunnar the Burgundian King, Brunhilde exercised tremendous power and influence, in the end transcending literature and inspiring Richard Wagner as he composed his ‘Der Ring des Nibelungen’ epic music dramas.

Hollywood has had a hard time adapting her story for the screen, however. Uli Edel’s ‘Sword of Xanten’ (2004) featuring Kristanna Loken and Alicia Witt was a flop, mainly because it was marketed as ‘the Nordic legend that inspired J.R.R. Tolkien to write the Lord of the Rings trilogy’ without even a quarter of Peter Jackson’s budget—not to mention storytelling talent.

But Brunhilde has found a different path through Marvel Studios, more recently, in Taika Waititi’s ‘Thor: Ragnarok’ (2017) and the Russo Brothers’ ‘Avengers: Endgame’ (2019). Portrayed by the monumentally talented Tessa Thompson, the character known as Valkyrie serves as a warrior and shieldmaiden of Asgard. Unfortunately, she lacks the complexities and ambitions that once got Brunhilde her own Wagner operas. Much like with Mulan and Boudicca before her, I cling to the hope that someday, someone will give Brunhilde the story she deserves.

‘THOR: RAGNAROK’ (2017), ©WALT DISNEY PICTURES/MARVEL STUDIOS

‘THOR: RAGNAROK’ (2017), ©WALT DISNEY PICTURES/MARVEL STUDIOS

The Girl and the Dragon

In Romanian folklore, there are stories of Ileana Simziana—the youngest daughter of a king who picked up a sword and went to fight in another king’s army so she might do her sonless father proud. In one version of the myth, Ileana is said to have gone against a mighty dragon. And that’s about all I’ve got.

Honestly, I just needed a mostly unrelated lady-and-dragon segue to squeeze Emilia Clarke’s Daenerys of House Targaryen, First of Her Name and so on into the conversation. In the HBO series, while she doesn’t pick up a sword until the last season and only against the army of the dead, the Mother of Dragons still fits the mould of a warrior queen by conquering enslaved cities to liberate them and by leading her armies across the east before she turns west to take the Iron Throne.

Following closely along the broad strokes of this archetype, Daenerys has a mission, a creed that propels her forward and against ancient adversities. She fights against injustice with a focus on breaking the chains of those enslaved by the wealthy and the cruel. While she starts out as a naïve and innocent girl, Daenerys experiences tremendous suffering before she rises with her dragons and reshapes parts of Essos, proudly donning the Khal’s victory braids as she takes her Unsullied and Dothraki across the Narrow Sea.

‘GAME OF THRONES’ (2011-2018), ©HBO/HOME BOX OFFICE

‘GAME OF THRONES’ (2011-2018), ©HBO/HOME BOX OFFICE

‘Game of Thrones’ (2011-2019) features more warrior women beside the silver-haired dragon queen—worth praising are Brienne of Tarth, stupendously portrayed by Gwendoline Christie, and fan-favourite Arya Stark, played by Maisie Williams. The former was loosely inspired by Joan of Arc, though George R.R. Martin has mentioned Eleanor of Aquitaine and Xena the Warrior Princess as building blocks for the phenomenal Brienne.

The latter drew on the sexual revolution and on the basis of feminism itself. In an interview with Rolling Stone, Mr Martin explained that he originally envisioned the Stark sisters as two opposing forces, with Sansa as the ‘romantic medieval ideal who dreamed of […] being the mistress of a castle and perhaps a princess and a queen’, and Arya as the counter force, chafing at the roles she was pushed into and favouring sword fights over sewing and singing.

‘GAME OF THRONES’ (2011-2019), ©HBO/HOME BOX OFFICE

‘GAME OF THRONES’ (2011-2019), ©HBO/HOME BOX OFFICE

Ultimately, the warrior queen quintessence as painted by Hollywood follows a simple but effective recipe which uses two or more of the following: the heroine fights aggressively when she has to; she is never merely a sidekick to any man; she usually belongs to an organization or a culture of other similarly minded women; there is some display of kinship and sisterhood with her own gender, as well, and she uses the classic warrior weapons and tools; she is independent and doesn’t need a man to save her, and in several instances, she lives in a or comes from a ‘lost civilization’.

In a commercially driven society that is inclined to sexualize and objectify female protagonists to absurd levels that degrade the story’s intended realism, the warrior woman has managed to tread a fine line that pleases and intrigues almost every audience. Yes, she is beautiful and downright hypnotizing to most, but her true appeal stems from her ability to purvey justified violence.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.