The sci-fi genre has been a staple of cinematography from the moment filmmakers were able to portray futuristic scenes and special effects. Naturally, when we think of sci-fi feature films, we’re inclined to balk at the budgets that are usually associated with such endeavours. These are stories that happen in alternate universes and in near or distant futures, and that means a lot of expensive worldbuilding.

‘Waterworld’, starring Kevin Costner, cost $175 million to make. J.J. Abrams’ ‘Star Trek’ almost $150 million. James Cameron’s ‘Avatar’ required a whopping $240 million to make. Even cult classics such as Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ and Ridley Scott’s ‘Blade Runner’ racked up budgets of $10 million and $23 million, respectively. I could keep going, but surely the point has been made. Science fiction on the silver screen is not easy to produce.

Sets. Costumes. Special effects. Make-up. CGI. Stunts. Models. Any good sci-fi implies a gargantuan amount of money and work—or does it?

Many independent screenwriters and directors rise against the current and defy all odds in order to create exceptional films within this genre, without spending much. Granted, not all of them succeed, but great things can be accomplished on micro-budgets, provided the screenplay is realistically crafted to adjust to its limited production sources.

CREDIT: SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

CREDIT: SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

‘Moon’, by Duncan Jones

In his debut feature film, Duncan Jones, otherwise known for ‘Source Code’ (2011), ‘Warcraft: The Beginning’ (2016), and ‘Mute’ (2018), managed to produce an astonishing story with very little money. It got him a BAFTA Film Award in 2010 for Outstanding Debut by a British Writer, Director or Producer, and for good reason.

In ‘Moon’, Sam Rockwell masterfully portrays Sam, a miner on a lunar base whose sole purpose is to extract helium-3. The story takes place in a distant future, when Earth’s people are struggling to find a source of clean energy, and Sam is one of the brave individuals who dedicates three years of his life to helping mankind on this mission. With only a talking computer to keep him company—that Space Odyssey nod is duly noted, by the way—Sam’s existence seems rather simple, linear and repetitive.

Everything comes to a sudden halt when he stumbles upon… another Sam. ‘Moon’ explores the mystery by keeping us anchored in Sam’s point of view. The décor, the special effects, the moon-walking suits, the gadgets—they all serve as anchor points to make the story real, which is exactly what ‘Moon’ feels like.

CREDIT: SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

CREDIT: SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

We’re trapped here, on Earth’s satellite, baffled by the existence of two Sams. We struggle to untangle the mystery, to make sense of what is going on. And by the time the end credits start rolling in, we find ourselves in awe of how much was done with only $5 million. While this figure doesn’t exactly qualify for a micro-budget, ‘Moon’ must be mentioned because it’s a master stroke among its costlier peers.

The acting is otherworldly, featuring only ten performers and Sam Rockwell taking up most of the screen time. The cinematography, executed by Gary Shaw, who also worked with Duncan Jones on ‘Mute’, is flawless. The film editing is signed by Nicholas Gaster, best known for ‘Coriolanus’ (2011) and Neil Gaiman’s ‘Mirrormask’ (2005). The score, penned by Clint Mansell, is exquisite, and it’s yet another building block, an integral part of the superb whole.

‘Moon’ manages to entice and thrill its audience through its cleanliness and simplicity, proving that big stories don’t always need big money to come to life.

CREDIT: HARVEST FILMWORKS

CREDIT: HARVEST FILMWORKS

‘Pi’, by Darren Aronofsky

With only $60,000 for his first feature-length film, Mr Aronofsky created a masterpiece. ‘Pi’ tells the story of a paranoid mathematical genius who lives in isolation, working on his homemade computer. Upon discovering a 216-digit number that seems to have serious implications for stock market fluctuations—as well as holding the pattern of a Nautilus shell and maybe even the name of God himself, Maximilian Cohen finds himself under siege.

Crippling headaches take over, while Wall Street figures try to get this number from him so they can use it for profit. It’s filmed in black-and-white, the start contrasts and the manic editing further contributing to the swelling paranoia that begins to take over Max. A mixture of conspiratorial surrealism and highly evolved mathematics, ‘Pi’ gives us a startling glimpse into a brilliant mind that is constantly pressed by its own human condition. Shot from Max’s perspective, it tells us about the dangers of searching for absolute order in the midst of our chaotic existence.

‘We didn’t want it to end up looking like “Clerks” and be all grey. We wanted it to be black or white. We were inspired by “Sin City” by Frank Miller—he just does white scratches on black ink’.

Matthew Libatique, best known for his camera work on ‘Black Swan’ (2010), ‘Requiem for a Dream’ (2000), and ‘A Star Is Born’ (2018), brought his cinematographic vision to ‘Pi’ whilst drawing inspiration from Frank Miller’s ‘Sin City’ graphic novel. Using Reversal film, which is frequently preferred in film schools, Mr Libatique was able to produce that absolute black versus white effect that makes ‘Pi’ so unique and powerful in its construction.

CREDIT: HARVEST FILMWORKS

CREDIT: HARVEST FILMWORKS

‘We didn’t want it to end up looking like “Clerks” and be all grey. We wanted it to be black or white. We were inspired by “Sin City” by Frank Miller—he just does white scratches on black ink’, Mr Aronofski said in a 1998 interview with IndieWire. Needless to say, ‘Pi’ was a mission accomplished in that respect.

Moreover, it was the launchpad of three cinematic modern masters. Mr Aronofsky went on to receive an Academy Award nomination, giving us masterpieces such as ‘Requiem for a Dream’, ‘Black Swan’ and ‘The Fountain’. He worked with Matthew Libatique for the first two, further pushing him into the spotlight, as ‘Black Swan’ eventually earned the cinematographer an Academy Award nomination of his own. Last, but not least, composer Clint Mansell got his career start with the score he created for ‘Pi’, later working with Aronofsky again on ‘The Fountain’ and ‘Black Swan’.

A little-known fact about ‘Pi’ is that Aronofsky took about five years to get the minuscule budget together. He raised money mostly from friends and family, after earning his MFA in film directing from the AFI conservatory. He and the crew filmed illegally in certain public spaces, since that normally required costly permits, which their micro-budget could not support. On top of that, post-production cost Aronofsky another $68,000, but it was well worth it. ‘Pi’ was a resounding success, and it was eventually bought by Artisan Entertainment for more than $1 million.

CREDIT: THINKFILM

CREDIT: THINKFILM

‘Primer’, by Shane Carruth

Former engineer and mathematician Shane Carruth made his debut into the cinematic universe with a very complex but exceptional feature film. ‘Primer’ tackles the accidental creation of a time machine, its story being led by two friends and inventors who end up in a web of their own making—doubles, paradoxes, deeply existential questions that desperately require answers.

It is also a sincere and quite unflattering portrait of mankind as a whole, as we’re often driven by needs but frequently giving into our wants. The invention of the time machine itself is an extraordinary feat, albeit the work of mere fortune. Its use, however, is driven by the characters’ personal desires. Mr Carruth’s study of them is compelling and ingenious, as each brushstroke serves to tell their innermost longings.

CREDIT: THINKFILM

CREDIT: THINKFILM

‘Primer’ would require multiple viewings, mainly because the engineering aspect is quite heavy in the script. The dialogue, rife with technical jargon, might be just as difficult to follow as the ensuing plot twists. Its end, however, brings with it a certain sense of reward. Watching ‘Primer’ more than once also gives us an opportunity to peel away at the layers of the story, as we discover details that we might miss at first.

But the most impressive aspect of ‘Primer’ comes from its ridiculously low budget. Production cost Carruth only $7,000, and it earned him the Grand Jury Prize and the Alfred P. Sloan Feature Film Prize at the Sundance Film Festival in 2004. Considering the story it conveys, along with its execution and editing, we can’t help but marvel at how much Mr Carruth was able to achieve with such a measly budget.

CREDIT: SNOWFORT PICTURES

CREDIT: SNOWFORT PICTURES

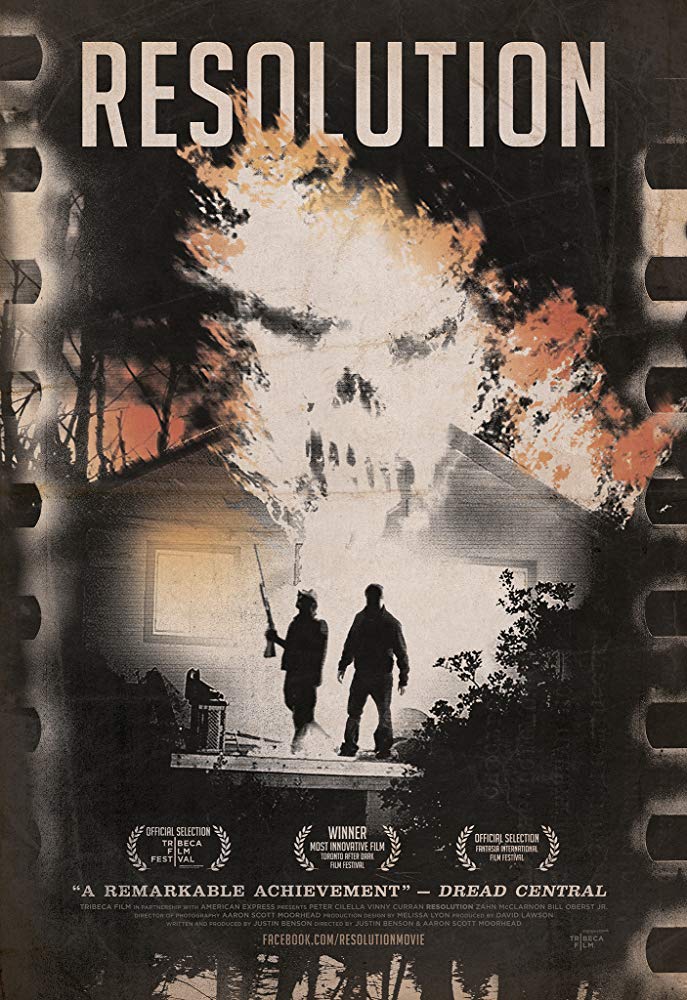

‘Resolution’, ‘Spring’, and ‘The Endless’, by Aaron Moorhead and Justin Benson

The focus of a good sci-fi film that can reach excellence, without millions of dollars’ worth of production money, is on compelling characters. It has always been about the people in the story, as already evidenced by the aforementioned low-budget oeuvres.

But there is no other film that better conveys the value of characters as well as ‘The Endless’ and its predecessors. It’s the third in a seemingly unrelated series of independent feature films in the sci-fi genre, written and directed by Aaron Moorhead and Justin Benson, and it is their best so far.

CREDIT: RUSTIC FILMS

CREDIT: RUSTIC FILMS

‘Resolution’ was their first project, back in 2012, and it cost the duo merely $3,000 to produce. It also captured the attention of genre fans thanks to its multi-layered screenplay and its character construction. ‘Resolution’ follows two friends, Michael and Chris, who inadvertently find themselves drawn into the script of an unseen entity that already has an ending in mind for them, deep in the heart of an Indian Reservation land near San Diego.

What starts out as one friend’s well-meaning attempt to force the other into sobriety ends up as a melange of strange happenings and eerie characters, all part of a story they cannot control. Simple in its production but extraordinary in its writing, ‘Resolution’ marked the beginning of a new era in sci-fi micro-budget features.

CREDIT: DRAFTHOUSE FILMS/FILMBUFF

CREDIT: DRAFTHOUSE FILMS/FILMBUFF

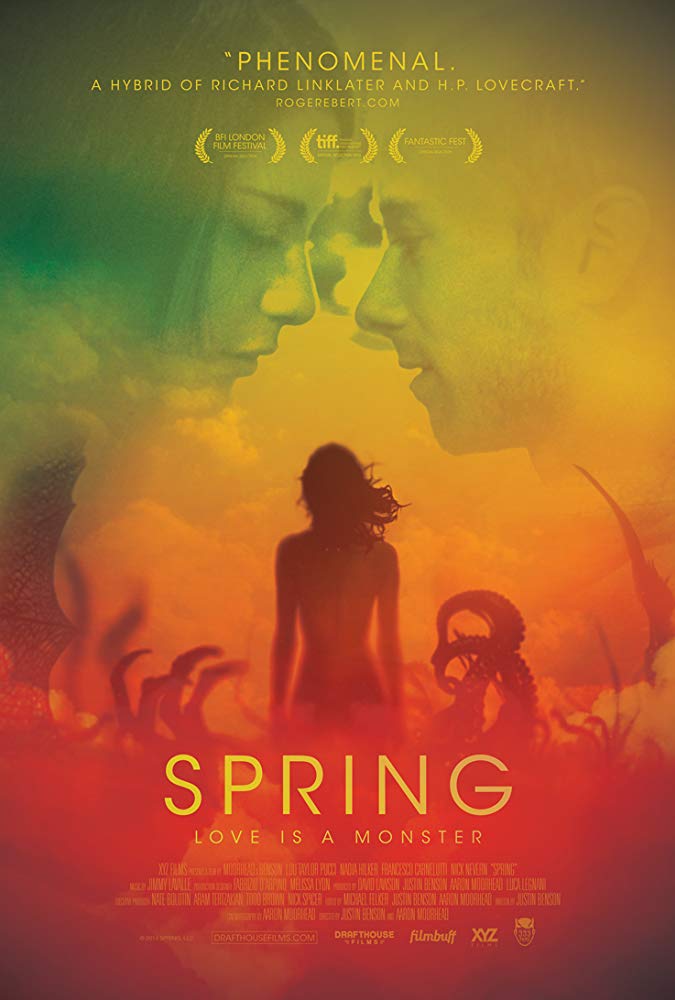

‘Spring’ followed in 2014, and a certain stylistic evolution could be observed, even though the film was made with small funds. Described as ‘”Before Sunrise” with a supernatural twist’ by Toronto-based programmer Colin Geddes, ‘Spring’ tells us about an American tourist and an immortal woman—Evan and Louise, who fall in love in a small village in Italy.

It fascinates through its charming simplicity, addressing love in the strangest of circumstances. At its core, it echoes the same concept that made Jerome Bixby’s ‘The Man from Earth’ (2007), a cult classic that we will lovingly address another time.

CREDIT: SNOWFORT PICTURES

CREDIT: SNOWFORT PICTURES

‘The Endless’ made it to Netflix after its release in 2018, and it was the very first time that a feature film bearing Mr Moorhead and Mr Benson’s signatures was made available to such a wide audience. Also marking their cinematic evolution, ‘The Endless’ is an exquisite blend of Lovecraftian horror and science fiction that might not dazzle with visual effects—it offers an incredible story instead, heralded by sincere characters.

Moorhead and Benson convincingly play the lead roles, as brothers with their own first names, who decide to go back to the UFO-cult that once raised them. After years of simply drifting through life, Aaron and Justin agree that it’s time to revisit the people that they used to call ‘family’, only to find that nothing is quite like it seems, and that there is something strange going on. With a clear connection to ‘Resolution’, the director duo has taken the unseen entity behind Michael and Chris’s ordeal and given it a whole new dimension.

CREDIT: SNOWFORT PICTURES

CREDIT: SNOWFORT PICTURES

We even see the two friends again, right here, in ‘The Endless’, which further serves as proof that Mr Moorhead and Mr Benson are able to effectively wow their audiences with little to nothing in terms of production value but so much where the screenwriting, the performances, the cinematography, and the editing are concerned.

Its production was more or less as much as one year’s tuition at an Ivy League college, roughly around the $40,000 mark, which is incredibly small given what this amount was able to produce. ‘The Endless’ was the absolute darling during its launch at the Toronto Film Festival, and it has earned every single glowing review—including its 93% Fresh score on Rotten Tomatoes.

There are many other indie sci-fi films out there that deserve our attention, and more are produced every year. The charm of Hollywood titans sometimes fades in comparison. Once in a while, a stunning piece of science fiction comes along, proving that one does not need millions upon millions of dollars in order to deliver excellence in futuristic storytelling.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.