A Hollywood maxim states that one can’t truly call themselves a film composer until they’ve had at least one entire score thrown out. Accurate or not, what is certain is that even the biggest names in the industry have had their work tossed aside in favour of another colleague’s work for one reason or another. The dreaded R-word spares – almost – no one.

In the first two parts of this series, we explore a select number of film scores that have been replaced during Hollywood’s Golden Age. Granted, replacements didn’t happen back then as often as they do in our times, however, historically, film scores have been substituted fairly regularly be it due to studio politics, personality clashes between the creators, desperate last-minute attempts to salvage an otherwise poor picture or simply because the composers brought in were concert composers who weren’t part of the studio system and didn’t really ‘get it’.

With the release of The Jazz Singer in 1927, the first feature-length motion picture to use a synchronized recorded score, the importance of the film soundtrack became apparent and thus studios started to commission original music. The next few years were spent experimenting and researching the best way to go about scoring a film. Legendary composer Max Steiner has stated that ‘background’ music was, for the most part, disapproved of before 1932 due to the fact that people were uncomfortable not being able to see where the sound was coming from.

‘THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME’ FILM POSTER

‘THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME’ FILM POSTER

The Most Dangerous Game (1932)

Max Steiner

W. Franke Harling

The Most Dangerous Game is a thriller adapted from a 1924 short story by Richard Connell, in which a deranged Russian Cossack hunter makes sure ships are wrecked on his island so that he can hunt the survivors for sport.

Producer Merian C. Cooper took charge at RKO Pictures during the Great Depression and was entrusted to go over all the projects that had accumulated with a fine-tooth comb and to greenlight the suitable ones. During that time, Cooper had two jungle adventures on his plate: King Kong (1933) – which required a large budget – and The Most Dangerous Game.

With a great reputation for delivering quality while being mindful of budgets, Cooper decided to test the feasibility of a jungle movie and went ahead with the production of The Most Dangerous Game. One of his ingenious ideas was to build film sets that were reserved for King Kong during the day and could be used for The Most Dangerous Game during the night.

MAX STEINER

MAX STEINER

Composer Max Steiner, who was Director of Music at RKO at that time, persuaded RKO’s bosses, who initially wanted to use ‘library music’ (old tracks), to go with original scores for these two movies. Steiner agreed to score King Kong at a reduced fee and Cooper said he would pay for the orchestra. Steiner already had a large workload on his shoulders, so W. Franke Harling was assigned to score The Most Dangerous Game.

Harling was well-known for having composed the music for A Light from St. Agnes, a popular jazz-oriented opera. Cooper, however, wasn’t pleased with his approach, complaining that his score was too ‘Broadway-light’ and unsuited for an adventure thriller.

Max Steiner was then begged to write a replacement score in only two weeks. Due to the very tight deadline on The Most Dangerous Game, Steiner had to work on this score almost in parallel with King Kong. And although it is often said that King Kong is the first great original film score of the ‘sound era’, some argue that this honour actually goes to The Most Dangerous Game, as it premiered sooner.

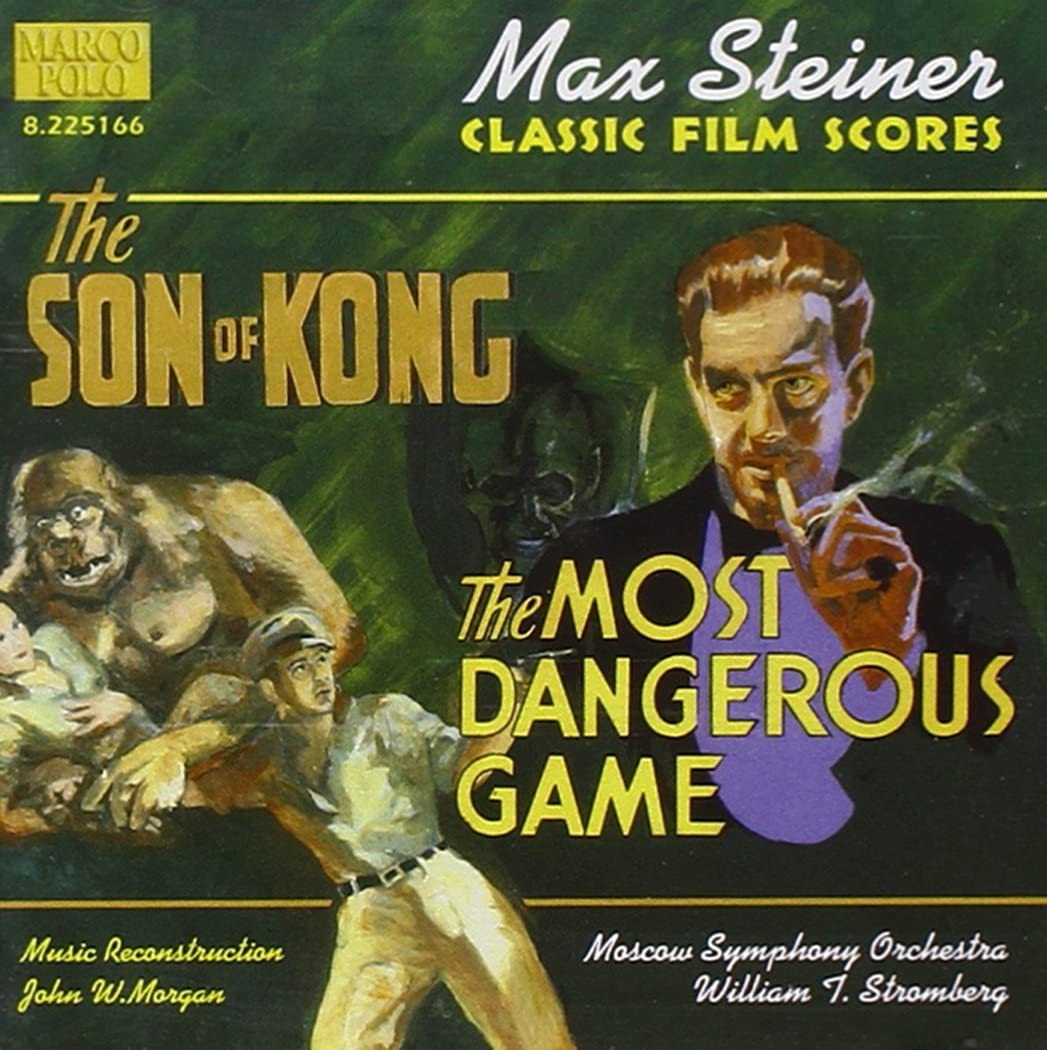

‘THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME’ AND ‘THE SON OF KONG’ SOUNDTRACK COVER

‘THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME’ AND ‘THE SON OF KONG’ SOUNDTRACK COVER

The music Max Steiner wrote for The Most Dangerous Game might sound all-too-familiar to most of us today, for it has been imitated countless times ever since. Steiner incorporated the leitmotif (Count Zaroff’s theme) he used throughout the film into ‘Russian Waltz’, a tune played by Count Zaroff at his piano in the film. This piece of diegetic music (AKA source music) was written by the composer himself. This ground-breaking technique of marrying the underscore with the source music would be used from then on in numerous films as a storytelling method. Furthermore, his music for the final chase scene is a masterclass in action and suspense scoring, employing techniques that are still used in sci-fi, thrillers, and horror movies today.

One of the problems faced by Steiner during this time was the small size of the orchestra that he had to work with. And while the players were some of the best in the business, the reduced number of the performers meant that the orchestra simply wasn’t able to convey the music penned by the composer in all its complexity so concessions had to be made. The recordings that exist today, performed by Moscow Symphony Orchestra and conducted by William Stromberg, are accurate reconstructions made by John W. Morgan for a full symphonic orchestra and are based on Steiner’s original handwritten sketches, thus reflecting the composer’s true musical intentions.

‘DON QUIXOTE’ FILM POSTER

‘DON QUIXOTE’ FILM POSTER

Don Quixote (1933)

Jacques Ibert

Maurice Ravel

In 1932, Austrian film director Georg Wilhelm Pabst embarked on the task of adapting Miguel de Cervantes’ celebrated novel, Don Quixote, a tale about an elderly man who goes mad from reading too many books on chivalry. He filmed three separate versions of the film, in English, French, and German. The legendary Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin would go on to play the title role in all three languages. Chaliapin was already familiar with the character, having portrayed him in Jules Massenet’s opera Don Quichotte in 1910.

The producers had reached out to five composers to write songs for this film, including Maurice Ravel, Marcel Delannoy, Manuel de Falla, Jacques Ibert, and Darius Milhaud. Little did the composers know that this was, in fact, a contest. Each of them was certain that their music would be featured in the film.

The contract signed in June 1932 specified a heroic song, a serenade, and a comic tune, with the deadline set for August and a warning that Chaliapin preferred not to have too many high Cs, Ds or E flats.

The winner was the great composer and master orchestrator, Maurice Ravel, who was asked to compose four pieces. The producers were happy with the choice, for Ravel was one of Europe’s most prominent composers and they were hoping that with his name attached to the project, together with French author’s Paul Morand – who provided the lyrics – the project would attract investors. Furthermore, Ravel had a proven affinity for Spanish music which is what the project required.

Ravel, however, had suffered health problems since 1919 and at this time his health was in decline, specifically after having suffered a head injury in a car accident which prevented him from putting the music that he heard in his head on paper. This, in turn, slowed his progress in delivering the music and Ravel was eventually fired as a composer, having completed only three songs. These would become the three-part song cycle Don Quichotte à Dulcinée and would cover other facets of the story than Ibert’s work. Chanson romanesque portrays the noble lunatic as a lover, Chanson épique as a holy warrior, and Chanson à boire depicts the protagonist as a drinker. Although his songs didn’t end up in the film, they have become some of the most performed songs in the Baritone repertoire. The songs were later published and were premiered on 1 December 1934 in Paris with baritone Martial Singher performing and Paul Perey leading the orchestra. These are Ravel’s final compositions before his death in 1937.

Pabst then turned to French composer Jacques Ibert, who, as it happens, was a friend of Ravel’s. Learning about the contest, both composers became outraged, Ravel even considering a lawsuit against the producers, an idea he later dropped.

Ibert provided four songs for Don Quixote, Chanson du depart, Chanson à Dulcinée, Chanson du Duc, and Chanson du mort. He also wrote a song for Sancho Panza, titled Chanson de Sancho. The song texts were written by Pierre de Ronsard and Alexandre Arnoux, with Ibert himself conducting the recording used in the picture. Ibert’s music ended up in all three productions and he went on to arrange the songs for voice and piano, which were later published under the title Chansons de Don Quichotte, for Voice and Piano.

‘THE GOOD EARTH’ FILM POSTER

‘THE GOOD EARTH’ FILM POSTER

The Good Earth (1937)

Herbert Stothart

Arnold Schoenberg

The Good Earth is an American drama based on Pearl S. Buck’s eponymous novel which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1932. It depicts the life of a Chinese family of farmers as they navigate through life’s up and downs.

The composer who was first approached with scoring this picture was none other than the great Arnold Schoenberg, the inventor of the twelve-tone technique, a revolutionary and highly-influential 20th-century compositional method. Schoenberg was living in California at the time in exile, having fled Europe to escape the Nazi regime. He was contacted by Irving Thalberg, the celebrated young producer at the Hollywood film studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Thalberg, who was a rather cultured movie mogul, met with Schoenberg at MGM’s studios in November 1935 and expressed his appreciation for the composer’s music. Thalberg explained that the music he imagined for this picture would be similar to Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht, op.4, which he had heard on the radio earlier that year.

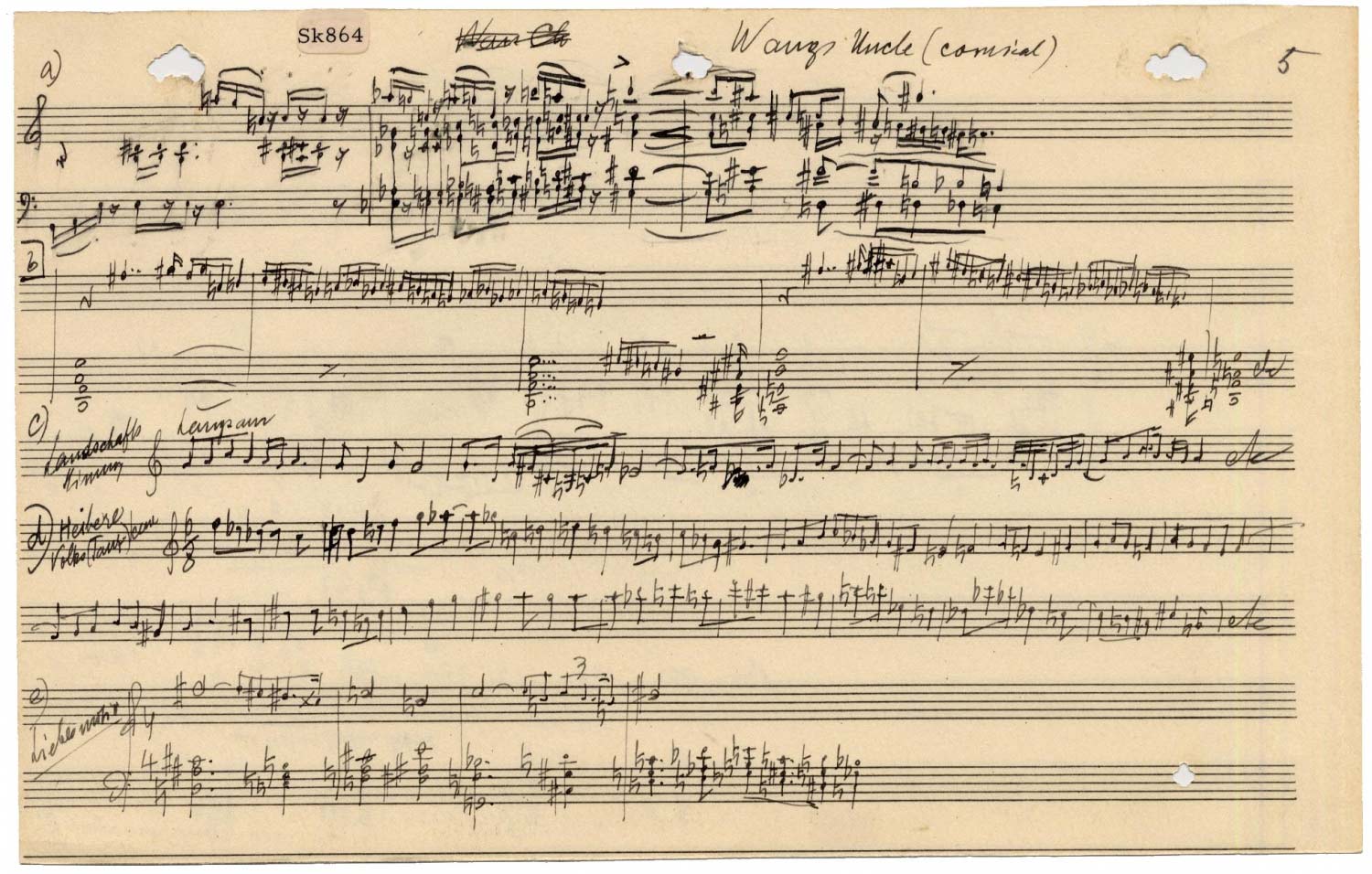

SCHOENBERG’S SKETCH FOR ‘WANG’S UNCLE’ ©ARNOLD SCHOENBERG CENTER

SCHOENBERG’S SKETCH FOR ‘WANG’S UNCLE’ ©ARNOLD SCHOENBERG CENTER

Unfortunately, Schoenberg got a little too involved in the project, long before signing any contract with the studio. He proceeded to carefully read the short novel that was sent to him by the MGM library and made numerous markings on its pages. Two of Schoenberg’s notebooks contain over thirty sketches of roughly worked out tonal, chromatic and pentatonic motifs and themes for The Good Earth. Among them are ‘a motif of an eventful growing crowd of people’, a motif to ‘the uncle of Ching’, a ‘lotus’ theme, a ‘fishpond’ motif, themes for ‘Wang’s Uncle’, ‘funeral/death’ motifs, motifs of a ‘turbulent folk scene in connection with the revolution’, motifs about the ‘fear of the Wang family because of the soldiers’, as well as a ‘pearl/wealth’ motif. It has to be noted that Schoenberg did all of this even before a second meeting took place.

Unaccustomed with Hollywood’s film-scoring process, Schoenberg requested full control of the soundtrack – including dialogue – and demanded a staggering fee of $50,000 for his services. He is also said to have requested to work directly with the actors and have the director shoot the film to match his music – not the other way around. The main stumbling blocks with contracting concert composers to score a picture were money and time, as they were used to their highly-priced concert music commissions and they liked to take their time to write the music. These were two issues that were not compatible with the film studios’ way of doing things since the production of a film was under a tight deadline – and so it remains to this day – and the studios had their own experienced composers that could do the work at a fraction of the price and in a short period of time.

The collaboration never came to fruition and three weeks after their initial meeting, Schoenberg addressed a letter to Thalberg expressing his disappointment with the former’s silent treatment.

Herbert Stothart and Edward Ward were eventually engaged to provide the music for The Good Earth.

‘THE THIEF OF BAGDAD’ FILM POSTER

‘THE THIEF OF BAGDAD’ FILM POSTER

The Thief of Bagdad (1940)

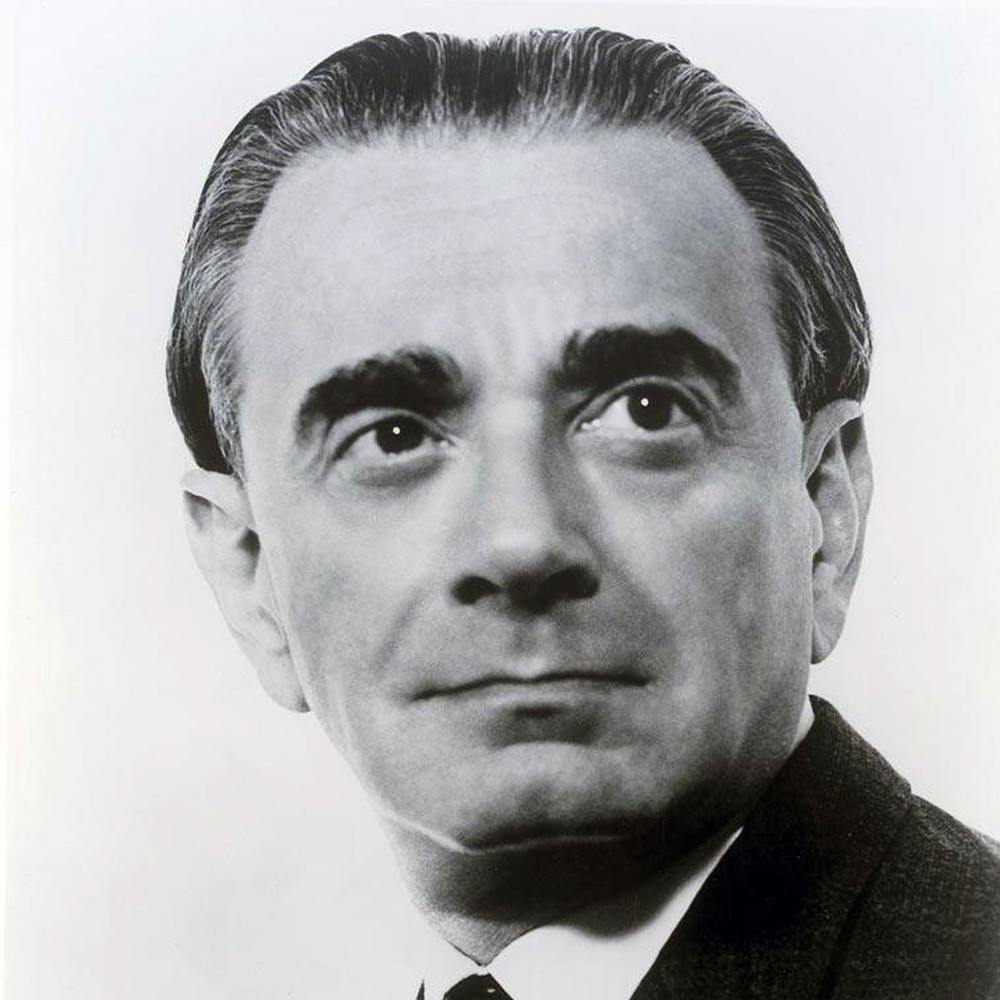

Miklós Rózsa

Oscar Strauss

The Thief of Bagdad is a 1940 film marketed at the time as an ‘An Arabian Fantasy in Technicolor’. The film was produced by the renowned director and producer Alexander Korda of London Films, who had long dreamt of remaking the 1924 silent film of the same name. The story takes inspiration from the classic Arabian tale One Thousand and One Nights, as well as the novel The Tower and the Elephant by Robert E. Howard, and features a classic hero, a villain, a love story, magic, and adventure.

Korda began working on the project early in 1939 and chose German filmmaker Ludwig Berger to direct the picture. Interestingly, the production team at London Films comprised almost entirely of Hungarian émigrés, including Alexander Korda and his brothers, director Zoltán Korda and art director Vincent Korda, screenwriter Lajos Biró, and composer Miklós Rózsa, who had already scored Knight Without Armour (1937) and The Four Feathers (1939) for the firm.

Alexander Korda was planning on hiring Rózsa once more for this film, promising him a significant increase in his salary – which, according to Rózsa, had been quite low up to that point – and that his contract would begin immediately. However, Berger insisted that they should instead bring Austrian composer Oscar Straus on board, as the pair had collaborated before on Ein Waltztraum (1925) and Les Trois Valses (1938). It was agreed then that Strauss would write all the pre-production music and Rózsa would provide ‘all the dramatic and colouristic music’. Rózsa had no choice at that point than to agree to this arrangement.

Strauss was taking a cure in the French town of Vichy at that time so he sent all his music to London by mail. A composer of waltzes and operettas, Strauss’ musical input proved to be unsuitable for the film, or as Rózsa himself put it, ‘It was impossible – typical turn-of-the-century Viennese candy-floss.’

The musical director, Muir Mathieson, was furious with the outcome and didn’t hold back in expressing his frustration during a tense meeting with Alexander Korda and Miklós Rózsa. While publicly siding with Berger on the issue of the music, Korda was unhappy with Strauss’ sketches as well and secretly instructed Rózsa to re-write the music and call him when he’s ready. A week later, Rózsa had the music ready and Korda had the brilliant idea of giving him an office next to Berger’s, where he had a piano installed. He then asked the composer to keep playing his music until Berger came out of his office. Rózsa started to work and play fortissimo in that office, and after three days, Berger finally came into his office and enquired about the music. After listening to a few of the pieces Rózsa had composed, Berger realized that this music was much better suited for the film.

MIKLÓS RÓZSA

MIKLÓS RÓZSA

A telegram was subsequently sent to Oscar Straus notifying him of his dismissal from the production. Strauss threatened to sue, stating that this incident was ruining his reputation, but soon had a change of heart after Korda paid him his fee in full.

Rózsa went on to compose the score and songs for The Thief of Bagdad, which would become instant classics. Due to the outbreak of WW2, the production was forced to move to California where the film was completed, a move which prompted Rózsa’s prolific Hollywood career.

The critically acclaimed film became a commercial success and earned four Academy Award nominations including Best Cinematography, Best Art Direction, Best Special Effects and Best Film Score, winning all but the award for Best Film Score.

Stella Lungu

Stella is the Editor-in-Chief of The Cinematic Journal. She is also the Managing Director of Wolkh, a PR, Marketing and Branding agency specializing in Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.