The Second World War didn’t just displace and kill millions of people. It reshaped the cinematic industry in many countries involved with the combat effort, and in some respects, it further emphasized the role of film as a propaganda medium. Despite the ravages of this infamous global conflict, however, the world of movies continued to evolve, to develop new techniques and editing methods.

The value of the story rivalled that of the actors’ performance, and the golden age of Hollywood continued to set new trends and deliver incredible stories onto the silver screen. Filmmakers from Europe, Mexico, Asia and Russia didn’t back down either, though each continent brought forth its own cultural identity and elements of style. Therefore, this next decade we’re about to delve into is rife with key moments that further shaped the cinema we know and love today.

1939: The Classics Emerge

There were many movies that made film history in 1939. To be honest, it was hard to pick the truly seminal ones, since each of these films is now considered a building block of cinema itself. ‘The Wizard of Oz’ (1939), directed by King Vidor, is at the top of the list. He remained uncredited at the time after replacing the already-credited Victor Fleming, who’d left the production to shoot ‘Gone with the Wind’ that same year.

‘Over the Rainbow’ is, to this day, one of the greatest song performances in history and an iconic scene. When MGM’s super-production was first previewed, the studio’s execs felt that the movie was too long, so a number of cuts were made. ‘The Jitterbug’ was among the casualties, and Judy Garland’s ‘Over the Rainbow’ almost got the boot, as well. Fortunately, wiser heads prevailed, going against this idea that people didn’t go to the movies to watch a farm girl sing against the black and white backdrop of Kansas. The most achingly lovely musical performance thus survived the final cut, and the song went on to win the Academy Award for Best Original Song.

‘THE WIZARD OF OZ’ (1939), ©METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER (MGM)

‘THE WIZARD OF OZ’ (1939), ©METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER (MGM)

Victor Fleming secured his pictorial immortality with ‘Gone with the Wind’ (1939), an ambitious and spectacular rendition of Margaret Mitchell’s eponymous book. But for a big picture that covers entire decades of the Civil War and the Reconstruction era, it’s strikingly short on spectacle, since the plot is more concerned with the romantic travails of Scarlett O’Hara and other characters. Much of the action, such as Leslie Howard’s night-riding raids with the Ku Klux Klan and even the deaths of major characters, happens off-screen.

Despite that, ‘Gone with the Wind’ delivers an unforgettable scene when Vivien Leigh’s Scarlett searches for Harry Davenport’s Dr Meade among a crowd of 16,000 wounded Confederate soldiers. This moment conveys the dreadful price that soldiers pay in wartime, as Scarlett realizes the extent of the suffering. There are 800 extras and about 800 more dummies on screen as the camera pulls back and up to take in an acre of open-air hospital from a godlike vantage.

‘GONE WITH THE WIND’ (1939), ©METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER (MGM)

‘GONE WITH THE WIND’ (1939), ©METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER (MGM)

The filibuster at the end of ‘Mr Smith Goes to Washington’ (1939) not only defined James Stewart’s screen persona, it also helped define how Americans would see themselves in the post-war era. Frank Capra’s cinematic masterpiece gives us Mr Smith as the quintessential American hero—boyish, energetic, naïve and idealistic, an innocent soul thrust into politics by a corrupt political machine that foolishly thinks he’ll be easy to manipulate. But in his crazed, desperate zeal during the filibuster, Mr Smith ends up representing the dark side of American idealism as it confronts reality. Capra’s films are widely regarded as corny and overly simplistic nowadays, though most critics fail to see how dark and subversive his portrayals of American life really are.

‘MR SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON’ (1939), ©COLUMBIA PICTURES

‘MR SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON’ (1939), ©COLUMBIA PICTURES

In 1939, 11-year-old Shirley Temple was topping the box office. Glamorous goddesses like Greta Garbo were considered ‘unwholesome’. The Hollywood Reporter had gone as far as to declare her ‘box office poison’, and yet Ms Garbo laughed in Ernst Lubitsch’s ‘Ninotchka’ (1939), and the whole of America went through a sudden spell of adulthood that lasted for months. Playing Nina Ivanovna Yakushova, a special envoy from Moscow in Paris, Ms Garbo scoffs at the sight of a fancy hat shop window. ‘How can such a civilization survive which permits their women to put things like that on their heads? It won’t be long now, comrades.’

‘NINOTCHKA’ (1939), ©METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER (MGM)

‘NINOTCHKA’ (1939), ©METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER (MGM)

1940: Of Comedy and Cartoons

Howard Hawks is at his most laconic and most eloquent with the arrest of Earl Williams scene in ‘His Girl Friday’ (1940). We find ourselves in the press room of the Criminal Courts building of a major American city. Cary Grant’s Walter Burns, newspaper editor, and Rosalind Russell’s Hildy Johnson, ace reporter, have just hit an exclusive pot of gold as John Qualen’s Earl Williams, convicted murderer and freshly escaped from death row, has picked the press room to hide in. It’s a brilliant fast-paced comedy sprinkled with typically Hawksian shots and intelligent narrative.

‘HIS GIRL FRIDAY’ (1940), ©COLUMBIA PICTURES

‘HIS GIRL FRIDAY’ (1940), ©COLUMBIA PICTURES

A key character that emerges at this point in history is Bugs Bunny in ‘A Wild Hare’ (1940). In their ‘Guide to the Warner Bros. Cartoons’, animation historian Jerry Beck and author Will Friedwald said it best: ‘The classic cartoon that solidified the personalities of Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd and became the blueprint for their future encounters.’ Furthermore, this film contains the first utterance of the famous line ‘What’s up, Doc?’.

1941: Citizen Kane

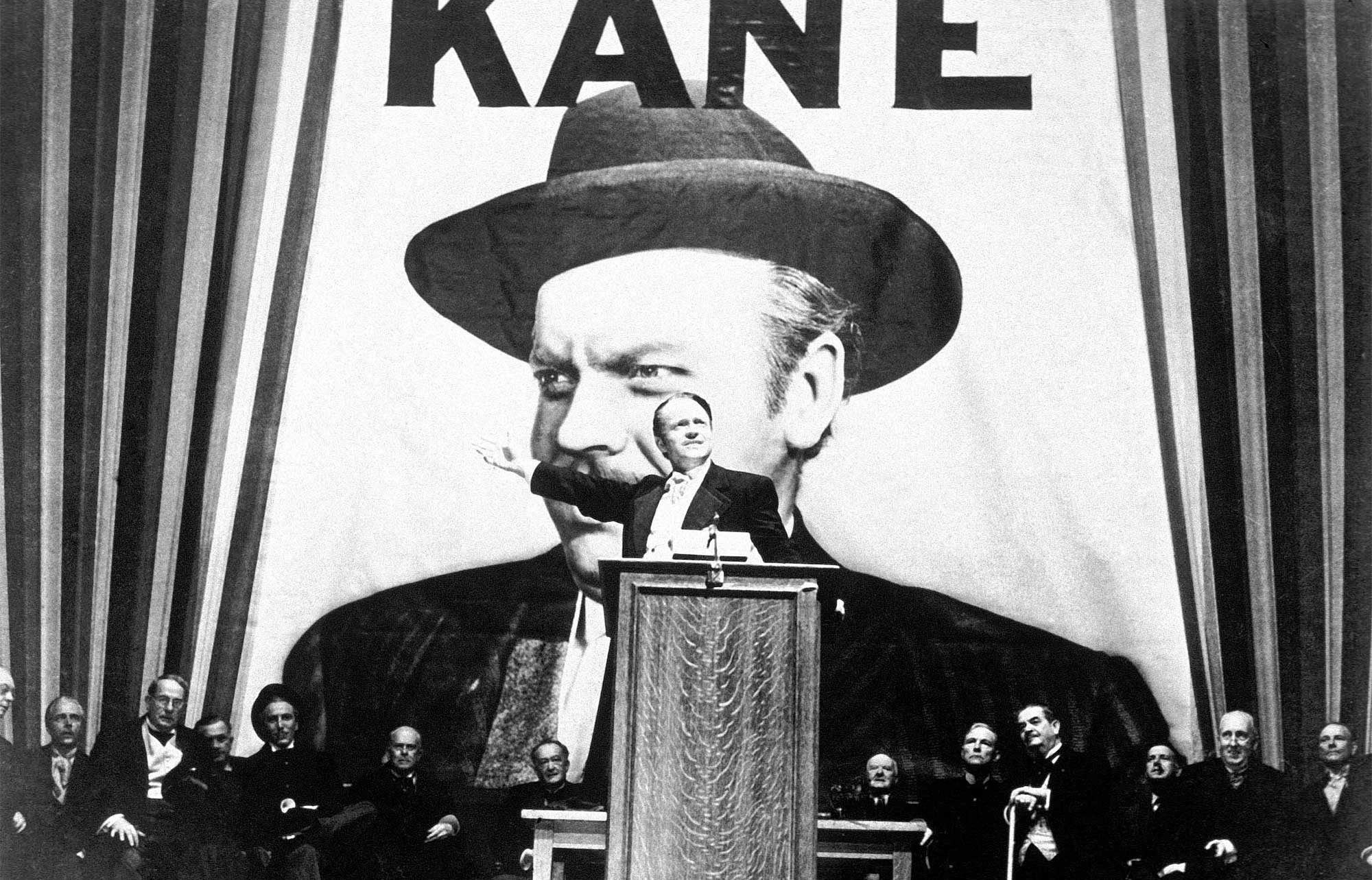

Of all the movies that made it onto the big screen, it was Orson Welles’s ‘Citizen Kane’ (1941) that embedded itself in the annals of history. It was his first feature-length oeuvre, which he co-wrote, produced, directed and acted in. Nominated for nine Academy Awards, it took home the trophy for Best Writing (Original Screenplay), which Mr Welles shared with Herman J. Mankiewicz, who also penned ‘The Wizard of Oz’.

Most importantly, it was the film’s encyclopaedic nature that doubtlessly impressed Jorge Luis Borges, who called ‘Citizen Kane’ a film that ‘teems with multiplicity and incongruity’, never more so than in its final moment, for the credits represent the true end—this final accounting of the story reconfiguring the cinema itself as a ‘catalogue raisonné’.

‘CITIZEN KANE’ (1941), ©RKO RADIO PICTURES

‘CITIZEN KANE’ (1941), ©RKO RADIO PICTURES

1943: Casablanca

Everyone remembers Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman in ‘Casablanca’ (1943), Michael Curtiz’s masterpiece. Their performances aren’t just exquisite. They’re the stuff of silver screen legends. ‘Here’s looking at you, kid’ is perhaps one of cinema’s most memorable lines, which Bogart’s Rick says to Bergman’s Ilsa.

But it’s the last speech that offers yet another defining moment, as Rick and Captain Renault agree to leave everything behind in Morocco and go off to join the Free French against the Nazis. The pair walk off into the foggy night to an unknown, but presumably legendary future. Bogart’s final words take the sting off what might come across as a downbeat and sentimental wartime sacrifice ending, since his character has bid the love of his life and his business farewell, but he says: ‘Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.’ Like all great endings, it’s also a beginning—of a story we can only imagine.

‘CASABLANCA’ (1943), ©WARNER BROS.

‘CASABLANCA’ (1943), ©WARNER BROS.

1944: A Year Full of Magic

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s ‘A Canterbury Tale’ (1944) gave us what could easily be described as the single greatest cut in the history of film. We begin with a quote from Chaucer, an illuminated manuscript, and a group of medieval pilgrims on a road through the Kentish countryside. In close-up, a hood is taken off a falcon, and the bird soars into the skies, watched by a noble falconer played by James Sadler. In a match-cut that skips 600 years, the falcon becomes a Spitfire, and we return to Sadler’s face looking up, only now he’s wearing a 1944 British soldier’s tin-hat, offering an astonishing visual effect.

The entrance of a femme fatale in a film noir is always a key moment, and ‘Double Indemnity’ (1944), one of the finest examples of its genre, does not depart from the rule. It is an exquisite example of film noir’s construction of femininity and a highlight in Barbara Stanwyck’s career, as she stands at the top of the stairs, covered only by a towel and seeming unattainable and domineering towards the aroused visitor. And then she comes down the stairs… While Ms Stanwyck certainly wasn’t the most beautiful actress of her era, she was definitely one of the most talented, as she manages to convincingly portray her character as both cold and engaging.

‘DOUBLE INDEMNITY’ (1944), ©PARAMOUNT PICTURES

‘DOUBLE INDEMNITY’ (1944), ©PARAMOUNT PICTURES

An unforgettable snippet of Hollywood’s golden age comes through the sizzling chemistry between Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, a pair that went on to tie the knot after Howard Hawks’ ‘To Have and Have Not’ (1944). The situation of the film is pure Bogart—a selfish man is forced by circumstances to commit to a cause. But the one who steals the show is Bacall in her hypnotic first ever performance. She was so nervous during the shoot that she tensed her neck muscles and dropped her chin in what would become known as ‘the look’, and yet she delivered one of the power lines of cinema: ‘You know how to whistle, don’t you, Steve? You just put your lips together and blow.’

‘TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT’ (1944), ©RONALD GRANT ARCHIVE/MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY 2009

‘TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT’ (1944), ©RONALD GRANT ARCHIVE/MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY 2009

1946: Camera Movements and Cannes

The crane was among Alfred Hitchcock’s favourite toys from the earliest years of cinema, but the suspense master’s use of it in the Cary Grant-Ingrid Bergman thriller ‘Notorious’ (1946) still ranks among its most memorable appearances. The famous crane shot occurs during a black-tie party at which Bergman’s Alicia is supposed to use a purloined key to access the wine cellar. It starts high above the party, peering down over a second-floor railing at the guests, then slowly descends to pick out Alicia. It moves even closer to reveal the key in her hand, giving us a truly meaningful camera movement that amplifies the plot.

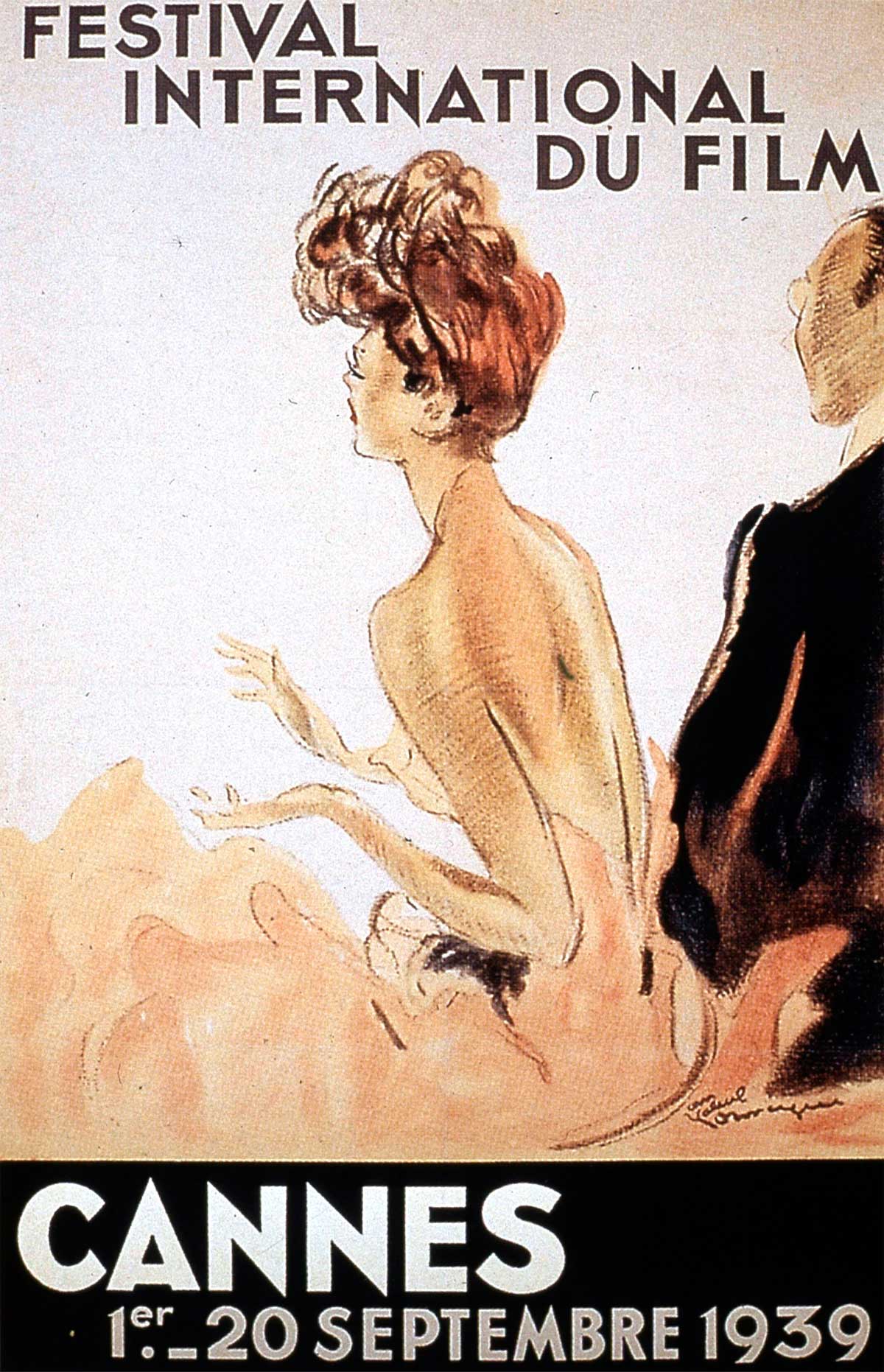

That same year, nineteen countries teamed up to take the first substantial step toward the creation of a global film culture by organizing the Cannes International Film Festival. The opening night was on 20th September 1946, seven years after its intended first date (cancelled due to the outbreak of World War II), and it marked the birth of a worldwide film culture with celebratory fireworks and film-star/soprano Grace Moore crooning the ‘Marseillaise’. There were numerous disruptions, including blackouts and Hitchock’s ‘Notorious’ reels projected in the wrong order, but nothing could dim the event’s roaring success.

THE ORIGINAL EVENT POSTER, ©FESTIVAL DE CANNES

THE ORIGINAL EVENT POSTER, ©FESTIVAL DE CANNES

1948: The Paramount Divestiture Decree

The federal government of the United States filed a lawsuit that became known as ‘United States vs Paramount Pictures, Inc. et al.’, charging the ‘Big Five’ studios (Paramount, MGM, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO) with violating antitrust statutes. The move came after complaints piled up from independent theatre exhibitors that the Hollywood studios’ chokehold on producing, screening and distributing films had created a monopoly that restrained free competition. Eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled that all studios had to divest themselves of their nationwide theatre chains.

Combined with dropping ticket sales and the growing proliferation of television sets, the ruling meant the loss of predictable and guaranteed theatrical income for the studios. It ultimately led to the physical dismantling and sale of studio backlots and warehouses about a decade later. Ironically, as the number of moviegoers declined in the ‘50s, it was the film corporations that ultimately benefitted from these sales, passing on the loss to independent theatre owners—the very entities that the Paramount decree had intended to protect.

1949: The Glory of Melodrama

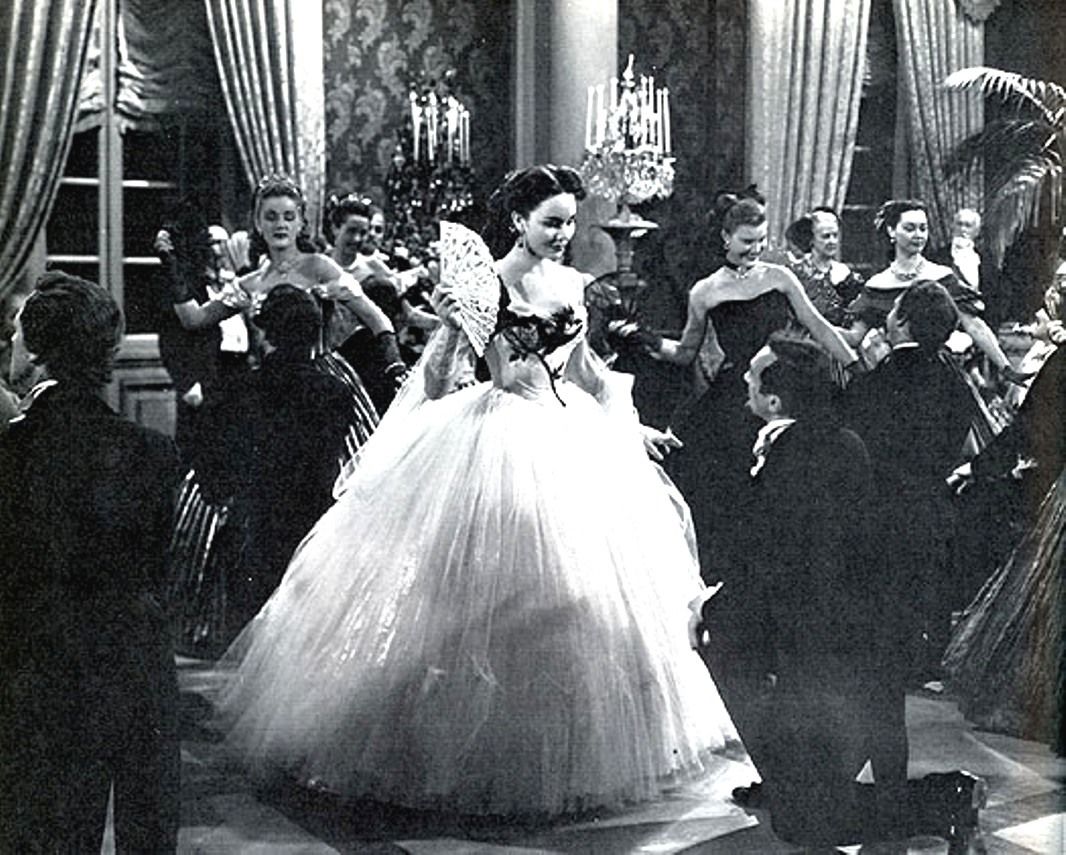

Vincente Minnelli was a master of both the musical and the melodrama, the one director who was able to display the close kinship between the two genres. His films are rich in dynamic and visually stunning set pieces of mounting tension and blissful release. It’s a cinema of ‘key moments’, and ‘Madame Bovary’ (1949) illustrates the peak of his powers with the ball’s kinetic sequence.

‘MADAME BOVARY’ (1949), ©METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER (MGM)

‘MADAME BOVARY’ (1949), ©METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER (MGM)

In this scene, provincial doctor Charles Bovary, played by Van Heflin, and his beautiful wife, Emma, beautifully brought to life by Jennifer Jones, attend a ball hosted by a nobleman. The entire moment is structured by the changing styles, tempos, and time signatures of the musical pieces played during the celebration—all composed by Miklós Rózsa, and Emma is pursued by Minnelli’s tirelessly moving camera. It ends with a regal order that every window in the ballroom be smashed, and Madame Bovary’s husband lurchingly descending onto the floor in pursuit of her. It is not just cinematically satisfying as a scene. It is socially embarrassing, intense, and therefore impossible to forget.

Jules R. Simion

Jules is a writer, screenwriter, and lover of all things cinematic. She has spent most of her adult life crafting stories and watching films, both feature-length and shorts. Jules enjoys peeling away at the layers of each production, from screenplay to post-production, in order to reveal what truly makes the story work.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.