We met recently with composer Nainita Desai at her home studio in London. Over the course of 75 minutes, the BAFTA Breakthrough Brit spoke about the process behind The Reason I Jump’ and the Oscar-nominated ‘For Sama’, her first big symphonic score for ‘Untamed Romania’, as well as the state of gender equality in the industry. With a successful career spanning over two decades, Nainita has been busy creating sounds and music for countless BAFTA, Oscar and Emmy honoured productions. The composer’s career has skyrocketed in recent years as she lent her composing skills to internationally acclaimed projects which showcased her versatile and experimental nature.

You were born and brought up in London by Indian parents. Has Indian music, with its exotic ragas and complex rhythms influenced your voice as an artist?

Yes, and no. I went to a Church of England school where I had violin and piano lessons and I wanted to be a singer, so I sang in all sorts of different choirs. I also had this schizophrenic life, being brought up as a Hindu at home. I had to go to Indian temple with my parents on Sundays and my mother forced me to get sitar lessons. [laughs] That was very good because there was a lot of discipline involved. My guru, Das Gupta, came from the Etawa Gharana. It’s a very oral tradition of music. So I’ve really learned to use my ears, more than anything.

NAINITA DESAI IN HER HOME STUDIO IN LONDON

NAINITA DESAI IN HER HOME STUDIO IN LONDON

There’s a centre in London called Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, which is The Indian Institute of Culture. When I was a teenager, my mother wanted me to go into Indian classical dance, but I went there and I was attracted to the tablas. I just love complex Indian rhythms and World rhythms, so for me, percussion and rhythm was a way in. And that has stayed with me in terms of my Indian heritage. I hear rhythm in a very different way. And that can be a good thing and a bad thing. Because when I’m writing, for example, string parts, the rhythms and the syncopation can be complicated for the Western string players. They’re very good at reading the dots, but when it comes to doing things rhythmically and instinctively, it can be challenging for some musicians. So I have to be careful.

Would you say you had a tough time breaking into the industry as a woman, and particularly, a woman of Indian descent?

Yeah, I did! One thing I would say is that I look at myself from the inside out, not from the outside in. I am who I am, I love music and I love film. It crosses all genders and ethic barriers. But I am very much aware that other people will look at me from the outside in, they’ll look at the colour of my skin and my ethnicity. And then they’ll want to put me in a box.

As a teenager I did have cultural and social pressures to have a formal education, so I did a degree in mathematics. And that was kind of my backup plan, if the music or the film thing didn’t work out.

I grew up loving film scores, all the way through the decades. I would be drawn to the power of film music when I watched new films with John Barry’s scores, and those beautiful melodies by Ennio Morricone and John Williams. Trevor Jones’s ‘The Last of the Mohicans’ and ‘Sea of Love’. But it was the stories more than anything and the storytelling in the music in those films that really captivated me and made me realize that what was that made me feel something was the music. But I had impostor syndrome. I felt that because I didn’t have a degree in music, it wasn’t something that I could do.

NAINITA DESAI’S STUDIO IN LONDON

NAINITA DESAI’S STUDIO IN LONDON

I did maths because I love the beauty of numbers. Funnily enough, having that discipline and formal education has stayed with me through my whole career because the way I approach writing music has maths in it in a very metaphysical way. When I construct a piece of music, they’ll be an inherent equilibrium to it, like a Yin and a Yang. But it’s not something that I consciously think about when I’m constructing.

As a teenager I was really into computers and programming. I did my thesis on the wave equation, which was coming up with a new form of sampling. I believe Yamaha employed it in their synthesizers at the time. So maths and technology are always there.

Speaking of mathematical structures, have you ever tried to write something based on the Fibonacci sequence or the Golden Ratio?

Yes, yes! It’s something I’ve been really interested in actually. I’ve studied fractals and created fractal design. It’s something that I want to integrate into a concept for my own album. I’m very much into crossing the bridge between technology and these mathematical constructs but in a very organic, human way. Connecting with people on an emotional level using music but also using mathematics is the essence of life in many ways. Maths is everywhere in nature.

I’ve worked on so many projects where I have to serve the film, the story and the director’s vision, where I have to adapt and work within those parameters and briefs. As media composers we learn to channel that in order to tell those stories, but when you’re working on your own music, you can write anything and that is one of the biggest challenges.

I can only assume it must be both exciting and daunting to work on your own project where there are no limitations to what you can do. Where do you start and where do you stop?

I know and I’m terrible with choice! I have a tendency to want to explore every possibility and that’s not a good thing. So having defined deadlines is great for me. When you’re working on your own project and you don’t have a deadline that’s a very dangerous thing. I’m definitely setting myself a deadline to work on this project in between other projects. I’m not going to tell you what it is though! [laughs]

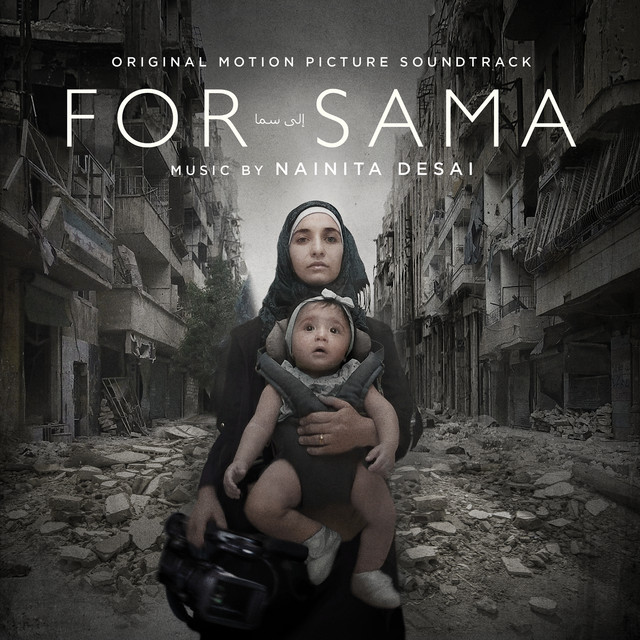

One of your most recent projects is the critically acclaimed ‘For Sama’, which won Best Documentary at Cannes, BAFTA, SXSW and was nominated for an Oscar. How did the collaboration with co-directors Waad Al-Kateab and Edward Watts come about and more specifically, what attracted you to the story?

I tend to gravitate towards the darker side of human life. I think I find it perhaps easier to express myself and to channel those emotions. Happiness doesn’t come that easily to me musically. But when I’m in my studio, it’s all about my process which is very immersive. I tend to inhabit the characters, the film, the story that I’m working on. But as soon as I’m out of my studio I’m a very happy, cheerful and social person, because I manage to contain it in the studio.

With regards to ‘For Sama’, Ed Watts was looking for a composer and I was recommended by a sound designer friend. I got sent some rough scenes in the very early stages of the edit which were incredibly powerful in their raw state and I just thought this was an astonishing story. I had to work on it.

When I watched the scenes, Waad was in the film and I was in total awe of her. I only had a few scenes to watch so I didn’t really know much else about it. I didn’t know whether she was dead or alive, as I didn’t have the full story. [‘For Sama’ is an intimate and raw account of Waad Al-Kateab, her family and friends’ experience during five years of the uprising in Aleppo, Syria.]

When the scenes are emotional, and people are crying and dying, you think, ‘I don’t need to overdo it, manipulate the audience with the music.’ You just don’t need it, it’s already there.

I went to a meeting to the edit suite and she was there, sitting on the floor laughing and I thought, ‘What?! You’re alive!’ I was quite moved emotionally when I met her. To have that personal connection with someone who lived it, filmed it, it’s her life and she’s the co-director. And she’s telling me how she wants the music to be. That was quite overwhelming. I felt a big responsibility on my shoulders to do her life story and the film justice. So when she’d say, ‘There’s a Syrian folk song that I grew up with as a child and I want a version of that for the end of the film.’, I said, ‘Yes, Waad, whatever you want.’

What instructions did you receive for the score?

The initial brief was to write a big, rich, symphonic score. Almost like a Hollywood contemporary orchestral score with electronics and synths. I wrote over eighty themes and Ed and Waad were editing with that. The edit actually lasted for 18 months, which is a huge amount of time. We were meant to edit the film in 12 weeks. The film grew organically. With 500 hours’ worth of footage you can almost make 500 films. It’s not a story that has a script. It’s one of those films that finds its voice in post-production.

After three months they paused. They had various viewings with exec producers. The film wasn’t quite working for them. There were lots of views and opinions being thrown around and eventually the idea came up where they thought this was an epic film with an epic story. But at heart, what is this film about? This film is the relationship between a mother and a daughter. She’s writing a love letter to her daughter saying why they stayed in Aleppo for so long and why they eventually left. When they made that decision, all the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle fell into place. And then of course, the music no longer worked with that narrative direction because it was too much for the images and the story.

NAINITA DESAI ARRIVES AT THE BAFTA BREAKTHROUGH BRITS CEREMONY. ©BAFTA/JAMIE SIMONDS

NAINITA DESAI ARRIVES AT THE BAFTA BREAKTHROUGH BRITS CEREMONY. ©BAFTA/JAMIE SIMONDS

We stripped it back to its essence, which is this human story. It’s about love, life, death, and laughter amongst this backdrop of horrific actions which are sadly still happening today.

I brought in a Syrian violinist who’s a refugee and who was living in Northern Italy at the time. That was the heart of Aleppo for me. And his playing was not this pure, classical, pristine, clean playing. It was this gritty, edgy, slightly raw playing, which reflected the aching heart of Aleppo.

The images by themselves are so overwhelming and powerful – everything is already there. It’s one of those situations where if you cross this fine line, the music can easily become redundant or worse, become kitsch and fall into absurdity. I thought it was brilliant how you wrote cues where there was just enough space to incorporate music, where the action wasn’t so tense.

It’s a very minimalist score. I think that’s one of the hardest things to do in film scoring, where as a composer you want to say, ‘Hey, look, I can write amazing music with huge orchestrations and big symphony orchestra’. And I’ve done that before, but ultimately, I felt I have to serve the film. When the scenes are emotional, and people are crying and dying, you think, ‘I don’t need to overdo it, manipulate the audience with the music.’ You just don’t need it, it’s already there. So I’m really subtly underscoring it. Restraint was hard to do but that was the direction that we took. I also think the way you choose not to have music is as important as where you do have music. To me, silence is music as well.

Trying to blend music with sound design so that it felt part of the soundscape was a direction that we found was working for the film. For example, there was bombing going on in one scene and with all the sound effects, I had this thumping sparse heartbeat sound. Sometimes you didn’t know whether it was the music or whether it was the bombing.

I love how you underscored those pure moments where there are glimpses of hope, where a child or the adults are laughing, or the pure joy of Waad’s friend when she receives a persimmon [fruit was very hard to come by during the war].

Her name is Afra. She’s lovely. I met her for the first time at the BAFTA awards. It’s so funny. When you work on a film, you get to know the characters intimately. I’m inhabiting the characters and getting into their minds and thinking about how they’re feeling and trying to express that. And then, when you meet them in real life you think, ‘Afra, I know you!’ And she’s like, ‘Who are you? I don’t know you at all.’ [laughs] It’s always a strange experience. I knew her from the film and she’s just full of joy and life. A really lovely woman. The same with Waad, Hamza and the girls. I know them well, like friends of mine.

For me, film is a transformative medium and that’s what I love about it. Something like ‘For Sama’ mobilizes people into wanting to do something about the situation. You can’t get more powerful than that. It can change your life, it educates you. Before ‘For Sama’, people were suffering from fatigue about Syria. People were getting bored and tired of seeing the same thing again and again. Especially here in the West, when you watch things through the physical barrier of the screen, whether it’s your mobile phone, computer screen or television, you suffer from that fatigue.

But they are real human beings. Middle class people living in Aleppo. This could be you or I. It humanizes people and that’s what’s so special about this film. I’m very proud to be associated with those kinds of projects that tell stories and can move people in such an amazing way.

THE BBC NATIONAL ORCHESTRA OF WALES DURING THE RECORDING SESSION FOR UNTAMED ROMANIA

THE BBC NATIONAL ORCHESTRA OF WALES DURING THE RECORDING SESSION FOR UNTAMED ROMANIA

If we compare two of the documentaries you scored recently, ‘For Sama’ and ‘Untamed Romania’, they had very different narrative arcs. In ‘Untamed Romania’, the story follows the four seasons of the year, each season containing smaller stories for all the different creatures living in the forests and waters of Romania. How did you approach scoring this documentary?

Oh, that was a joy! And it couldn’t be more different from ‘For Sama’. I love scoring natural history. Whereas with ‘For Sama’, the images are leading and the music is supporting, ‘Untamed Romania’ was kind of the opposite in some respects. You have to really lead the storytelling through the music. The music dominates a lot. And I think in natural history music has a very important, powerful role in telling the story.

For ‘Untamed Romania’ they wanted and had the budget for a big and rich symphonic score. And also something that we don’t have much in contemporary scoring these days: melody. Lately, I’ve been asked less and less to write lyrical sweeping melodies. And I grew up loving melodies. When people think of film and TV music, what stays in people’s minds are the tunes. And so it was a great opportunity for me to just use lots of melodies and write a very thematic score.

It’s based loosely on a year in the life of a family of bears. You see the bears in their different forms from baby cubs, to big fierce creatures, battling away with wolves and lazing around in the summer. I really wanted to have a theme for the bears, the same theme in different forms. And then a theme for the seasons, in four different forms.

They also wanted to bring out the magical side of Transylvania. That slight, kind of mystical, magical forest. The wolves of Transylvania, those old legends. I wrote a piece that has the spirit of those old ancient legends.

The difference with this project is that it was very fast and intense. On ‘For Sama’ we worked for eighteen months, and with Untamed Romania I think I had five and a half weeks to write eighty-eight minutes of music, a week to record with musicians and a week to mix. I recorded it with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales. Because I was on a fairly limited budget and quite short of time, I didn’t want to record in Eastern Europe. I also wanted to stay in the UK because I wanted to record the whole band together.

Having all seventy-three musicians playing together was just the most incredible sound and experience. And they’re used to playing together live concerts as well, that’s why I chose that particular orchestra. Whereas session musicians, when you’re in a studio, it becomes a very technical exercise in terms of precision and accuracy. Which you have with the BBC NOW Orchestra as well but it was a different experience.

THE BBC NATIONAL ORCHESTRA OF WALES DURING THE RECORDING SESSION FOR UNTAMED ROMANIA

THE BBC NATIONAL ORCHESTRA OF WALES DURING THE RECORDING SESSION FOR UNTAMED ROMANIA

Can you tell us a bit about the scoring process for ‘Untamed Romania’?

I got picture lock. That was great because when I score a film like that I tend to want to write it chronologically from start to finish. When I’m composing the music I want to experience it in the way the audience is going to experience it. And take them on this emotional journey with highs and lows and dynamic marks. I also wanted to utilize the whole orchestra, including the woodwinds, which tend to get neglected. Things like the flutes and the oboes really helped with the mystical aspect of the score. There are a few electronic cues as well, using samples. And that’s more for the underworld, when you go beneath the ground.

You know, some projects can be very stressful. Even though I was up against it timewise, the team were a joy to work with. When you’re working with directors and producers who really understand what you’re trying to do and they’re loving it, it motivates you even more. I had a great music team as well. My assistant and my orchestrator and conductor, Alastair King, were fantastic. When it all comes together, it’s just a joyful process.

It looks like we’re heading towards a positive direction in terms of more and more women working in film. Looking at this year’s Oscars alone, Hildur Guðnadóttir won Best Original Score for Joker, Eímear Noone conducted at the Oscars, five other composers, yourself included, were involved in Oscar-nominated films, and so on. Is the change palpable to you at this point? Has it had a significant impact on your work in the past say, two or three years?

I definitely noticed a change in terms of more and more female voices coming up and people in the industry wanting more female composers. And not just paying lip service to it, but they’re actually putting their money where their mouth is. Maybe initially it’s been as a token gesture, but I think that when you see the diversity, the quality and the originality of music being produced by women, people go, ‘Oh, you know what? Yeah. Women can do this.’ Which may come as a surprise to some people [laughs], but at least it’s then encouraging them to give more opportunities to women composers. I think that there are still very low percentages, but we have to give it time. It’s not going to happen overnight.

Since I started in the industry, I’ve definitely noticed a difference. I’ve been working away hard for over twenty years writing music and no one really paid much attention to that. Not that I needed attention, but I definitely feel that in the last three years I have been given more opportunities. And not just because I’m a woman, but because I’m a composer.

NAINITA DESAI

NAINITA DESAI

When I started I had virtually no female role models that were film composers. There was Rachel Portman, Shirley Walker, who was not really truly recognized at the time, and I think Debbie Wiseman, but there was virtually no one else. My female role models were people like Laurie Anderson and Kate Bush.

I think one of the reasons why it’s been difficult for women is that traditionally, technology has always been a very male-dominated area. But now, in universities and colleges, women are taking up these courses. 50% [of students] are male and 50% are female. Women are embracing technology. In this day and age, you can’t be a media composer unless you embrace technology. Universities like NFTS (National Film and Television School) and the Royal College of Music, are actively looking for women for their screen composition courses.

There’s one thing that I don’t agree with and that’s when you have female directors, which we’re seeing more and more coming through, you think that because you’re a female director you should automatically employ a female composer. I think you should be free to take on whomever you want, male or female. But I think it’s more powerful when men in positions of power champion women.

And female directors shouldn’t just make stories about female-focused stories. We want to see women making sci-fi and horror and mainstream movies. I think that’s when we’ll get real change in the industry. I want to see a female director directing a Bond movie. I think we’ve come close to it with Pinar Toprak scoring a Marvel film. It shouldn’t be big news. I just want to be a composer. I don’t want to be a female composer.

©SUNDANCE

©SUNDANCE

In 2019 you were on a roll, working on all these fantastic projects and it looks like in 2020 you’re heading in the same direction. Are there any future projects we should be on the lookout for?

I’ve just finished ’The Reason I Jump’, which had its world premiere at Sundance, and it won the Audience Award: World Cinema Documentary prize. It’s going to be released theatrically in the UK later on this year. It’s based on the bestseller book, The Reason I Jump by Naoki Higashida, which was written by a thirteen-year-old Japanese boy who is nonverbal autistic.

The film focuses on four/five people who are all nonverbal autistic and they’re in different parts of the world. It’s narrated by this young Japanese boy who talks about his experiences of being autistic and trying to make the audience understand what it feels for him to be autistic. It’s all beautifully filmed in 70mm and the whole soundtrack is created in 360 Dolby Atmos sound.

It’s a high concept score that blurs the line between sound and music in the film. It took us a while to find the path, but one of the early ideas which we still carried right through to the end was that they’re nonverbal. I wanted to give the nonverbal characters a musical voice. For example, I took a few key phrases from the English translation of the book, translated them into Japanese and then deconstructed the phrases and broke them down into syllables and consonants, then reconstructed them vocally in a very fragmented, broken, disjointed way. Autistic people see the detail in objects before they see the whole picture. So musically, I translated that into very fragmented little pieces of the jigsaw puzzle, which eventually all come together and flow together as one.

Another external expression of autism is that they like repetition. Autistic people may sometimes rock backwards and forwards because it makes them feel better. It’s like a cathartic release. So repetition and loops is something that I brought out into the music as well.

NAINITA DESAI WITH THE LONDON CONTEMPORARY ORCHESTRA

NAINITA DESAI WITH THE LONDON CONTEMPORARY ORCHESTRA

I brought in a cellist from the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Elizabeth Wicklander, who is autistic. Her contribution was very authentic, very personal and sensitive. She came to the studio and we had a couple of sessions together.

I brought in Daniel Pioro, who’s Johnny Greenwood’s violinist, and who is used to experimenting, just like the London Contemporary Orchestra are. Instead of bringing in musicians right at the very end, in a more traditional process of scoring, with this I was bringing in different types of musicians at a very early stage and experimenting with the human voice.

For example, I would set parameters in which I would write the music on the spot with the cellist and I’d say, ‘I’ve got seven notes and I want you to play a note, only change when I tell you to change the note, and when I point my finger upwards, I want you to go up a tone, and if I point it downwards, I need you to then go down a tone on the next bar.’ And so I wrote a foundation base drone and then we would layer up tracks on my direction so it was like generative composing within set parameters. It was a really interesting way of composing and creating textures. It was fun for the musician and me because we didn’t quite know what was going to happen.

I’m also finishing off a series for Netflix Originals, called ’Bad Boy Billionaires’ and a fifteen-part natural history documentary series for Quibi, called ‘Fierce Queens’, where each episode focuses on a different female species of the animal kingdom. Another series I’m working on is ’My Grandparents’ War’ for Channel 4, where they take these famous actors and go on very personal journeys exploring the roots of their grandparents and the roles that they played in various wars around the world. It’s very emotional.

I’m also working on ‘Enslaved’. It’s a six-part series executive produced by Samuel L. Jackson and his wife. It’s about the history of slavery.

Stella Lungu

Stella is the Editor-in-Chief of The Cinematic Journal. She is also the Managing Director of Wolkh, a PR, Marketing and Branding agency specializing in Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.

An Interview with Anna Drubich

Anna Drubich is a Russian-born composer of both concert and film music, and has studied across…

A Conversation with Adam Janota Bzowski

Adam Janota Bzowski is a London-based composer and sound designer who has been working in film and…

Interview: Rebekka Karijord on the Process of Scoring Songs of Earth

Songs of Earth is Margreth Olin’s critically acclaimed nature documentary which is both an intimate…

Don't miss out

Cinematic stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridiculously Effective PR & Marketing

Wolkh is a full-service creative agency specialising in PR, Marketing and Branding for Film, TV, Interactive Entertainment and Performing Arts.